The Exodus Pharaoh: Part II – The Egyptian Evidence

Photo: Asiatic name rings from the temple of Seti I at Kanais (Photo: © Talbot Smith, 2024)

<- The Exodus Pharaoh: Part I – The Candidates

The Exodus Pharaoh – Part II: The Egyptian Evidence

In Part I, we explored the various theories as to the identity of the Exodus Pharaoh, and the options span a broad period of time, covering approximately five hundred years. The situation in Egypt, and in Canaan, varies significantly over that time period, and so before we look at the archaeological evidence, it may be useful to have a basic understanding of the historical setting.

A Brief History

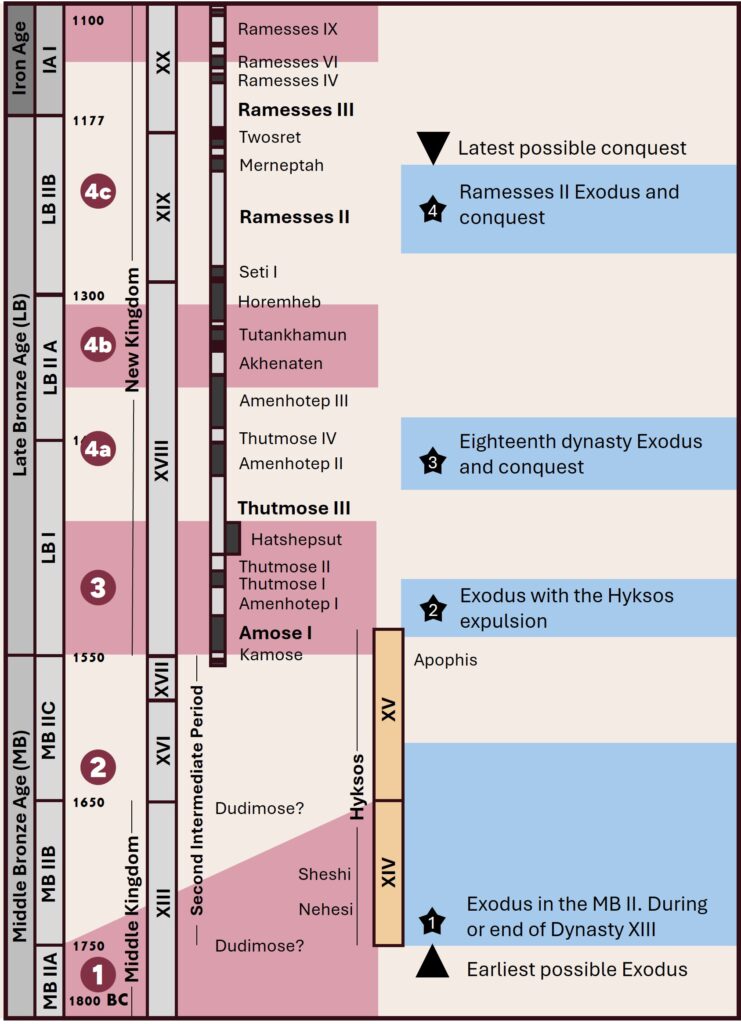

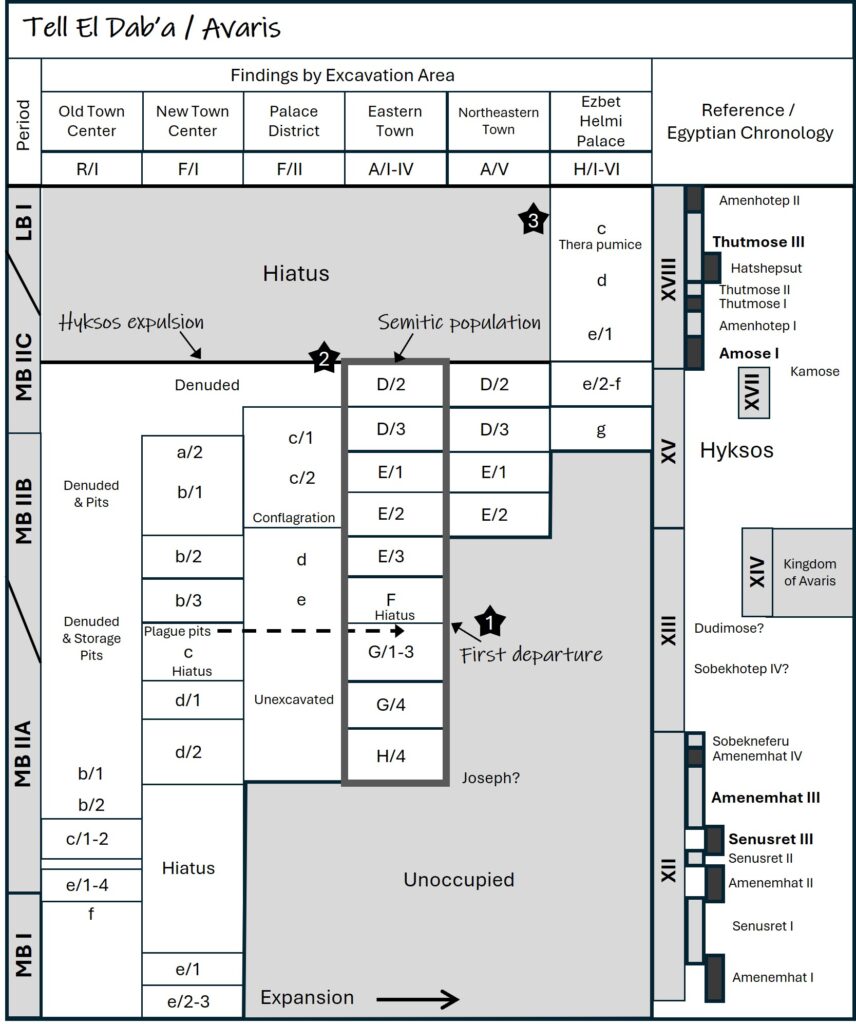

A detailed history of the events in those five hundred years is not required. However, what I think would be helpful is an understanding of the major phases of the relationship between Egypt and Canaan that existed in that time period, and an assessment of how an Exodus might fit in that context. In terms of the relationship between Egypt, Canaan, and ultimately Israel, I would identify four major phases, with the fourth having three sub-phases as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Historical Periods in Canaan and Egypt relating to the Exodus. Image © Talbot Smith

Phase 1: The End of the Middle Kingdom

I have previously associated Joseph with the Twelfth Dynasty Pharaoh Amenemhat III, and the sojourn of the Israelites in Egypt would have begun at this time. Amenemhat III was succeeded by his son Amenemhat IV, who reigned for nine years and was in turn succeeded by his sister Sobekneferu, the first female Pharaoh, for another five years. So ended the Twelfth Dynasty. If we associate Joseph with the vizier Ankhu, as I and others have proposed[1], we will find him still active in the early days of the next dynasty, the thirteenth[2].

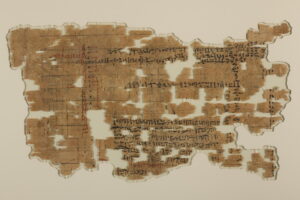

Figure 2: Papyrus Brooklyn 35.1446 (Photo: The Brooklyn Museum)

We know from Egyptian records, such as the Papyrus Brooklyn, that there were large numbers of Semitic slaves in Egypt at this time, as indicated by the list on the Papyrus Brooklyn. The front (recto) of the papyrus is linked to the time of the vizier Ankhu and his son Resseneb, and the reverse (verso) contains a list of ninety-five servants, forty-five of whom have Asiatic, i.e., Semitic names. This list is of a later date than the front side and comes from the time of Sobekhotep III. It may indicate that the Israelites were already enslaved at that time. Alternately, as the possibility exists that the owner of the slaves in question, a woman named Senebtisy, is the widow of Resseneb, these slaves may be captives from Egyptian campaigns in Canaan, or they may have been sold into slavery as Joseph was. Regardless, this papyrus documents a significant Semitic presence in Egypt prior to our earliest possible Exodus date.

Somewhere in the middle of the Thirteenth Dynasty, central authority disintegrates, and we find multiple Pharaohs ruling in Egypt. Recall from Part I that Artapanus remarked that by the time of Sobekhotep IV, “many were ruling in Egypt”. Interestingly enough, Sobekhotep IV is attested in both Upper and Lower Egypt,[3] suggesting that perhaps he ruled the entire country either briefly or indirectly, as a “great” king would rule over many lesser kings. As part of the disintegration that marks this dynasty, we see many very short reign lengths. While Manetho records this as a single dynasty, it may in fact reflect multiple parallel dynasties. In this general chaos, it’s not hard to imagine that a Pharaoh would arise who “did not know Joseph” (Exodus 1:8). One of the consequences of this situation is that we have very little in terms of written records. We do not have a complete list of Pharaohs and can only guess at key elements of the history. It is in this context that we place the critical quote from Manetho by way of Josephus:

“There was a king of ours whose name was Timaus. Under him it came to pass, I know not how, that God was averse to us, and there came, after a surprising manner, men of ignoble birth out of the eastern parts, and had boldness enough to make an expedition into our country, and with ease subdued it by force, yet without our hazarding a battle with them.” (Against Apion, I 14:75)

This quote reports two critical events: First, under a Pharaoh generally identified as Dudimose[4], there was a significant calamity that rendered Egypt defenseless. Second, at that moment of weakness, Egypt was invaded from the east. The source of this invasion was actually the northeast, and specifically Canaan. These invaders would rule Lower Egypt for more than a century and come to be known by the Egyptian term for foreign rulers: Hyksos.

Given the general chaos associated with the Thirteenth Dynasty, and particularly the latter part of that dynasty, it would not be surprising if an event such as the Exodus was not passed down to us in Egyptian records. Of course, the above quote from Manetho may in fact be a record of exactly that event. The defenselessness of Egypt at this moment also means that the Egyptians would be in no position to pursue the Israelites into Sinai or intervene in the later conquest of Canaan. In my opinion, this period is a perfect backdrop for the Exodus from Egypt and is perhaps the best fit for the biblical narrative. It also fits the two hundred fifteen year sojourn of the Israelites in Egypt according to the Septuagint (Exodus 12:40, LXX). We will consider the evidence for the Israelite presence at their point of departure, Avaris, later in this Part II.

Phase 2: Canaan in Egypt: The Hyksos

Josephus translated the term “Hyksos” as “shepherd kings”, but today we understand the term to mean “rulers of foreign lands”. Continuing the quote from Josephus above (quoting Manetho):

“So when they had gotten those that governed us under their power, they afterwards burned down our cities, and demolished the temples of the gods, and used all of the inhabitants after a most barbarous manner; nay, some they killed, and led their children and their wives into slavery. At length they made one of themselves king, whose name was Salitis; he also lived at Memphis, and made both the upper and lower regions pay tribute, and left garrisons in places that were most proper for them.” (Against Apion, I 14:76-77)

The tradition from Manetho is very much that of invasion. Some however would argue that instead this reflects the Semitic population of the delta rising up and creating an independent kingdom. Egyptologist Donald Redford argues that the sudden insertion of a completely urbanized Canaanite culture, in contrast to an existing Egyptianized Semitic culture, is more supportive of the invasion model.[5] The situation is further confused by the presence of two consecutive dynasties at Avaris, usually numbered the Fourteenth and Fifteenth. The names that we have for these Pharaohs are incomplete and likely garbled in translation, but several of the names are clearly Canaanite in origin. Most would make all of these rulers of Canaanite origin, but David Rohl would go so far as to assign a Minoan or Pelasgian Greek origin to the rulers of the Fifteenth Dynasty based on the remains of Minoan frescos found at Avaris.[6]

Whether Minoan or merely Canaanite, clearly a group of rulers from outside of Egypt would ‘not know Joseph’. However, if they were Canaanites, would they enslave a population of fellow Canaanites already dwelling in Egypt? If we place the birth of Moses in the time of Sobekhotep IV as suggested by Artapanus, they may have already been enslaved by the time the Hyksos arrived. Unlike more modern times when slavery was limited to foreign populations, in ancient times it was common to make slaves of people within the same culture (cf Exodus 21:1-11). The quote above from Manetho clearly references enslavement of the local population. Thus, it would be reasonable to place the Israelites time as slaves in this period. The presence of the Hyksos capital at Avaris also fits with the Exodus narrative and Moses’ and Aaron’s frequent meetings with Pharaoh, meetings that would have required a long journey if the Pharaoh was reigning from Thebes.[7]

A late Nineteenth Dynasty papyrus contains a sort of folk tale about the beginnings of the war that ended in the Hyksos expulsion. While scholars such as Redford would dismiss this document as entirely unhistorical,[8] I believe there is a kernel of truth at least in the historical context given at the beginning:

“Distress was in the town of the Asiatics, for Prince Apophis – life, prosperity, health! – was in Avaris, and the entire land was subject to him with their dues, the north as well, with all the good produce of the Delta. Then King Apophis – life, prosperity, health! – made him Seth as lord, and he would not serve any god who was in the land [except] Seth. And [he] built a temple of good and eternal work beside the House of the [King Apo]phis – life, prosperity, health! – [and] he appeared [every] day to have sacrifices made … daily to Seth.” (Papyrus Sallier I)[9]

The identification of Seth as the principal god of Avaris is another link to Canaanite culture, Seth being associated with Ba’al.[10] The temple of Seth in Avaris was likely originally constructed at the very beginning of the Hyksos period, and not in the reign of Apophis, the second to last Hyksos Pharaoh.

At this point we should turn our attention to the situation in Canaan. We have no Egyptian records for Canaan in this period due to the general lack of records and the confinement of the native Egyptian dynasties to the area of Thebes (modern Luxor). However, archaeology reveals a picture that aligns with that recorded in Deuteronomy and Joshua. At the time of Joseph’s arrival in Egypt, Canaan consisted of a largely pastoral population and a few unwalled settlements. However, as time passed these settlements would expand, both in number and in size. By the time of the Hyksos period, Middle Bronze IIB and IIC, the cities of Canaan would boast impressive fortifications, and could aptly be described as “fortified up to heaven” (Deuteronomy 1:28).[11] Furthermore, these cities would experience a wave of destructions at the end of the Middle Bronze Age (end of MB IIC). We will discuss this in Part III.

Considering both the political situation in Egypt and the archaeology of Canaan in this period, we have another good fit for the situation as described in Exodus and also for the later conquest. Here I should note that an Exodus just before the arrival of the Hyksos, or the very end of our Phase 1, would result in a conquest during the Hyksos period. Thus, the evidence just discussed for the situation in Canaan would apply equally to an Exodus in either Phase 1 or Phase 2.

Phase 3: Back to Normal

Ahmose, the first Pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty would ultimately succeed in expelling the hated Hyksos and reuniting Egypt under his sole rule. Egypt was however still in a bad state and it would take many years for it to fully recover. At least fifty years after Ahmose’s victory Hatshepsut, the female Pharaoh, would commission the following inscription:

“I have restored that which was ruins, I have raised up that which was unfinished since the Asiatics were in the midst of Avaris of the Northland, and the barbarians were in the midst of them, overthrowing that which was made, while they ruled in ignorance of Re.” Speos Artemidos Inscription, Lines 35-38 [12]

This indicates that reconstruction was ongoing even into her reign. Consequently, Egyptian interaction with Canaan was limited in this, our Phase 3.

From the most ancient history of Egypt, going back to the Old Kingdom and the age of the pyramids, we have mention of Egyptian campaigns in Canaan. These campaigns might best be described as raids. The Egyptians would proceed to Canaan, conquer a city or district, take plunder of material goods, livestock, and slaves, and promptly return to Egypt. There seems to have been no attempt to maintain any kind of governance of Canaan between these incursions. With the advent of the Eighteenth Dynasty, this age old pattern resumes. Following the expulsion of the Hyksos, Ahmose is known to have besieged Sharuhen and perhaps other cities in southwestern Canaan. Ah-mose son of Eben, who recorded the siege of Sharuhen, continued his service into the time of Thutmose I where another campaign is recorded:

“After this (Thutmose I) went forth to Retenu [Canaan and Syria], to assuage his heart throughout the foreign countries. His majesty reached Naharin [the kingdom of Mittani in north Syria], and his majesty – life, prosperity, health! – found that enemy while he was marshaling the battle array. Then his majesty made a great slaughter among them.”[13]

It is not known how Thutmose I reached this far north. He may have marched up the coast through Canaan, or he may have taken his army by sea to Lebanon and marched north from there. What we do know is that his target was Naharin, otherwise known as the kingdom of Mitanni, the other major power that was seeking an empire in Syria, Lebanon, and Canaan at that time.[14]

Unfortunately, we have very little information on these campaigns, and specifically no mention of either Pharaoh encountering an entity that we might identify as Israel in Canaan. However, given the limited details and the apparently limited area of these incursions, this is not surprising. Israel could easily have been present in Canaan, and particularly in the central highlands, and not encountered either Pharaoh. From Part I, we do not have a candidate for the Exodus Pharaoh in this period and, if anything, would be looking for evidence of the conquest if it had happened as late as the time of the Hyksos expulsion as proposed by Josephus, Africanus, and Eusebius. We will consider the conquest evidence in Part III.

Phase 4: Egypt in Canaan: The Empire

With the death of Hatshepsut, Thutmose III became the sole ruler of Egypt, and he immediately turned his eyes toward Canaan. In the first year of his sole reign, he defeated a Mittani-backed Canaanite coalition at the battle of Megiddo and, following a successful seven-month siege of that town, received the submission of a large number of cities, particularly those whose nobles had been trapped inside. Thutmose III recorded his victory in the great temple of Karnak in Thebes (modern Luxor), where he lists one hundred nineteen places with the following header:

“List of the countries of Upper Retenu [Canaan] which his majesty shut up in the city of Megiddo the wretched, whose children his majesty brought as living prisoners to the city of Suhen-em-Opet, on his first victorious campaign, according to the command of his father Amon, who led him in excellent ways.” (Karnak Temple, Pylon VI)[15]

Not all these places are cities, and many defy identification to this day. My interpretation of the list is that it is a mix of cities that submitted to Egyptian rule and a travel itinerary. Some of the names translate as “meadow” or “stream” and there is a sense that Pharaoh is perceived as having conquered everywhere he set foot. The list almost certainly encompasses more than the cities represented at Megiddo on that first campaign. What is significant here is the taking of the children of the rulers of these cities as hostages to ensure their continued submission, while also educating these children in Egyptian ways to tame, as it were, the next generation of rulers. This was not just a raid. This time, Egypt was here to stay.

Thutmose III would campaign in Canaan for fifteen of the next eighteen years, and his son Amenhotep II would campaign there in his years seven and nine. Some of these “campaigns” seem to have been just to collect tribute, while others were to resolve rebellions, and others still were directed farther north in Lebanon, reaching as far as the Euphrates where Thutmose III claims to have set up a stele next to that left by his grandfather, Thutmose I. Amenhotep II records that he took over 2,200 prisoners in the campaign of his seventh year, but this pales in comparison to what he records for his ninth year:

“His majesty reached the town of Memphis, his heart appeased over all countries, with all lands beneath his soles. List of the plunder which his majesty carried off: Prices of Retenu: 127; brothers of princes: 179; Apiru: 3,600; living Shasu: 15,200; Kharu: 36,300; living Neges: 15,070; the families thereof: 30,652; total: 89,600 men; similarly their goods, without their limit; all small cattle [sheep and goats] belonging to them; all (kinds of) cattle, without their limit; chariots of silver and gold: 60; painted chariots of wood: 1,032; in addition to all their weapons of warfare, being 13,050; through the strength of his august father, his beloved, who is thy magical protection, Amon, who decreed him valor.”[16]

The total of 89,600 is likely an exaggeration as this would have been nearly the entire settled population of Canaan at this time as estimated by archaeological surveys.[17] Whatever the correct number, this represented a significant oppression of the Canaanite population.

Phase 4a represents the period of the subjugation of Canaan by Egypt with campaigns by four generations of successive Pharaohs, from Thutmose III to Amenhotep III. However, from the later reign of Amenhotep III through the reigns of his son Akhenaten and grandson Tutankhamun, no campaigns are recorded. This is our Phase 4b. Canaan remained very much under Egyptian control, but more loosely so. The Amarna letters of this time period reflect infighting between the various cities and with a group known as the Apiru or Habiru. Many pleas to Pharaoh for help in defending his vassals and restoring order seemingly go unheeded.

Following the Amarna revolution of Akhenaten and the subsequent restoration of the primacy of Amun by Tutankhamen, the Eighteenth Dynasty comes to a close with power transferring to a series of generals. First Horemheb, and then Ramesses I, founder of the Nineteenth Dynasty. With this transition comes a return to campaigning in Canaan and further north into Lebanon where Ramesses II will fight the famous battle of Qadesh. This final Phase 4c is very much like 4a with a strong Egyptian presence in Canaan and no evidence of the turmoil that would accompany an Exodus or conquest.

The important takeaway from Phase 4 is that the Egyptian presence in Canaan during this period was significant and continuous. We also have some of the best records for any period in Egypt from the numerous temple inscriptions of these Pharaohs. And we have two of the most powerful Pharaohs in all of Egyptian history in Thutmose III and Ramesses II at exactly the spots where Theories Three and Four place the Exodus.

Most secular archaeologists will place the Exodus in this Phase 4c, and specifically in the time of Ramesses II, while simultaneously claiming that the stories of the Exodus and conquest are much later fictions, written down only in the time of King Josiah or later. In doing so, they cite an almost total absence of archaeological evidence to support an Exodus and conquest in this timeframe. This brings up a very interesting question: How do you confidently date something that didn’t happen? How can you be so sure about this dating in the absence of evidence to support it? The answer, I believe, is two-fold. First, there is a strong tendency among archaeologists to date the beginning of something immediately before the first evidence of that thing. In this case, the emergence of a people group known as “Israel” immediately before the mention of that name on the Merneptah stele. This is certainly the intellectually defensible position, but it also explains why we regularly see headlines along the lines of, “New discovery pushes back X by hundreds of years.” The earliest evidence today is simply the earliest evidence we have found so far. Second, they have seized on the mention of Ramesses II in Exodus 1:11, a position that, beginning with Ussher, and continuing even today, was championed by Christian theologians and also earlier “biblical archaeologists” and in particular Albright.

With this historical framework, it is now time to consider the evidence left to us by the Egyptians.

The Archaeological Evidence from Egypt

The Merneptah stele is the earliest generally accepted reference to a people called “Israel” in Egyptian records. Given the tendency of archaeologists to place the beginning of something immediately before the earliest evidence for that thing, and considering that Ramesses II was the father of Merneptah, it makes sense for them to place the Exodus and conquest in that time frame. But is the Merneptah stele really the only reference to Israel in all of Egyptian history? It is the only generally accepted reference, but if we are willing to look closely, there are indications that Israel was in contact with the Egyptians, in Canaan and Transjordan, much earlier.

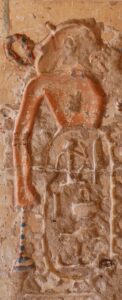

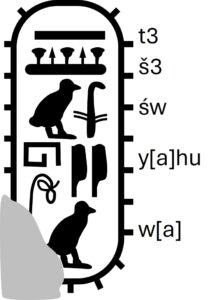

Figure 3: The Asher name ring from Kanais (Photo: Talbot Smith, 2024)

Asher

In a 2022 article, Pieter van der Veen notes references to the names of three of the Israelite tribes in Egyptian topographical lists of Dynasty Eighteen and Nineteen.[18] A name spelled “y-s-r” appears in a list of toponyms (place names) in the rock-cut temple of Seti I (father of Ramesses II) at Kanais (See Figure 3).[19] Some have argued that this spelling is a reference to Ashur (Assyria). However, Simons, the great cataloger of these lists, notes that Ashur is typically spelled with a double “s” whereas this entry only has a single “s”.[20] Furthermore, the context is a list of locations that form an itinerary leading from central Lebanon south into northern Israel. The preceding name ring seems to indicate Qadesh of Naphtali, north of the Sea of Galilee, and the following name ring is clearly Megiddo. Considering this information, van der Veen suggests that the location in question is to be found in the Jezreel valley or toward the coastal area near Acco. A location north and west of Megiddo would be consistent with the territory of Asher as described in Joshua 19:24-31, and thus, he proposes that this name ring represents the Israelite tribe of that name. If we accept the identification of this location as Asher, then at least that tribe must have been settled in their allotted territory before Ramesses II ascended his father’s throne.

Reuben

Figure 4: Ruins of the temple at Soleb (Photo: Francis Frith, 1862)

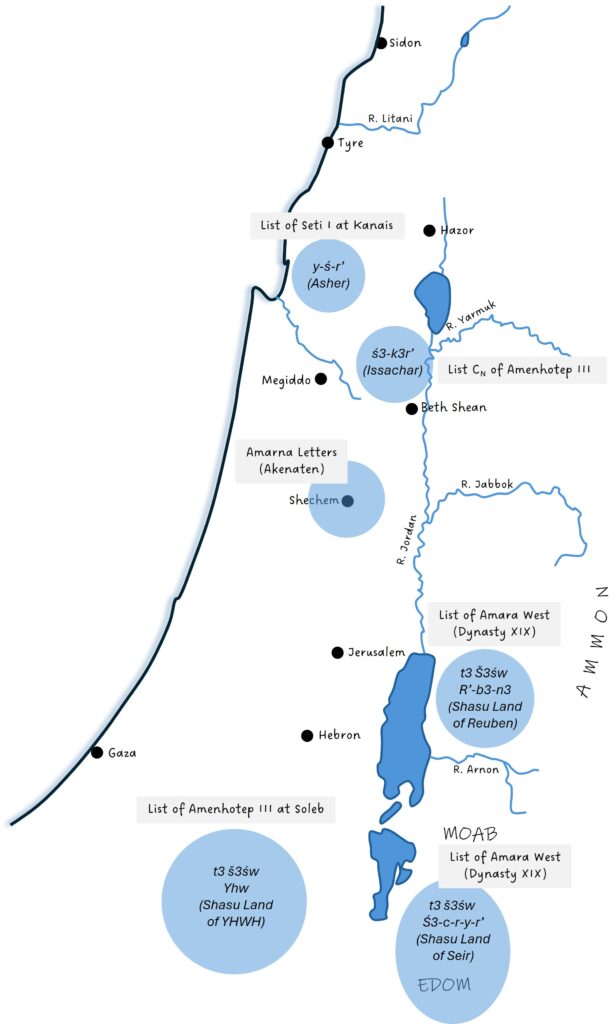

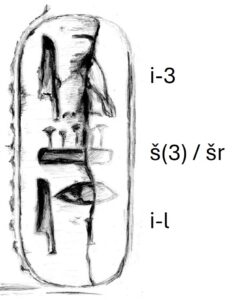

The name “t3 Š3św R’-b3-n3” appears in the topographical lists of Amarah West in Nubia (modern Sudan). These lists are believed to have been commissioned by either Seti I or Ramesses II.[21] The hieroglyphs “t3 Š3św” denote the “Shasu land”, or Bedouin land. Thus, the translation is “Shasu land of R-b-n”. The lists at Amarah West were likely copied from earlier lists of Amenhotep III at Soleb, 50km / 30mi further south. The Soleb list contains only three names, with a fourth name no longer legible. The Amarah list contains all three names from the Soleb list and three others, including the land of R-b-n, or Reuben, for a total of six. Immediately following R-b-n on the Amarah list is the name Shasu of Seir, or rather Edom. Consequently, it is reasonable to place the land of R-b-n in the lands granted to the tribe of Reuben, specifically, east of the Jordan and to the north of the river Arnon (Numbers 32:33-38), and van der Veen does so. This identification then places the tribe of Reuben in their settled territory no later than the time of Ramesses II, and, if the Amarah lists were indeed copied from Soleb, by the time of Amenhotep III (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Egyptian name rings relating to Israel. Adapted from van der Veen (2022), p30, and Bimson (2025), p178

Figure 6: The Shasu of YHWH name ring from Soleb

Another name that appears on the Amarah list is “t3 š3św yhw”, translated “Shasu land of Yahuwa”[22]. This last part is none other than the tetragrammaton, YHWH, the name of the God of Israel. Moreover, this name is one of the three that also appear at Soleb, meaning that a group of Bedouin who worshiped YHWH were known as early as the time of Amenhotep III. Van der Veen places this group in the south, specifically in the Negev or on the borders of the Sinai.[23] While a specific tribe is not named, no group other than the Israelites is known to have worshiped YHWH. If we place Israel in Canaan at this early date, this location would refer to the tribes of Judah and Simeon.

Issachar

The third tribe that can be found in Egyptian records is Issachar, spelled ś3-k3r’in a list (known as CN) of Amenhotep III found at his mortuary temple at Qom el-Hettan, on the west bank of the Nile opposite Luxor, site of the famous colossus of Memnon. Van der Veen argues that the placement of Issachar in this list is not inconsistent with a location in the Jezreel valley in the area allocated to them in Joshua 19:17-23.[24] Thus, we have three of the twelve tribes of Israel appearing in Egyptian records as early as the reign of Amenhotep III, or seventy-five years prior to Ramesses II.

Labaya

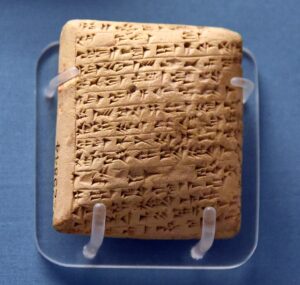

Figure 7: Amarna Letter (EA) 252, British Museum. Letter to Pharaoh from Labaya (Photo: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin via Wiki Commons)

One of the greatest finds in Egyptology is the Amarna Letters, a group of clay tablets written in Akkadian cuneiform and stored at Akenaten’s capital of Amarna. These tablets contain the correspondence of Akenaten and his father Amenhotep III (and perhaps his son Tutankhamen) with their vassals in Canaan and with other kings as far away as Assyria and Babylon. One of the prominent characters in these letters is a man named Labaya, the “mayor” of Shechem, who, while a vassal of Pharaoh himself, is at war with the other Canaanite vassals of Pharaoh. Given the location, some have equated him with Abimelech, the son of Gideon (Judges 9), while David Rohl, in a New Chronology context, equates him with Saul.[25] The name means “Lion of [Deity Name]”, but the deity is not actually specified. David Rohl has proposed that Labaya means “Lion of YHWH”. If he is correct, we have additional evidence of YHWH worshipers, this time in the heart of Israelite territory, as defined in the book of Joshua. Putting the name aside, a strong leader operating from Shechem is very much consistent with what we would expect from the Israelites during or after the conquest, be that leader Joshua, Abimelech, Saul, or someone else.

Habiru

Also prominent in the Amarna Letters is a group known as the Apiru or Habiru. Habiru, when pronounced, sounds a lot like “Hebrew”, and in the early twentieth century, the presence of these Habiru was considered a strong argument for an early Exodus and conquest. Throughout the Amarna correspondence, the Habiru are wreaking havoc, capturing cities, and generally causing trouble. Much as we would expect the Israelites to do as they conquered new areas of Canaan. However, by the second half of the twentieth century, the association of the Habiru with the Israelites had fallen out of favor as new scholarship made the connection increasingly tenuous. Today, we understand the Habiru to be landless people on the fringe of society that might be identified as brigands and who often acted as mercenaries. In this context, the majority view is that ‘not all Habiru were Hebrews, and not all Hebrews were Habiru’, but that there was an overlap between these designations. Thus, while a connection is not ruled out, we cannot look at these groups as a definitive indication of an Israelite presence.

Habiru groups do appear in the Bible, notably in three places: First, in Judges 9:4, Abimelech hired “worthless and reckless men” to follow him. These would be Habiru mercenaries. Second, in Judges 11:3, we see that “worthless men banded together with Jephthah and went out raiding with him”. This makes Jephthah a Habiru leader. Finally, when David fled from Saul, it is noted that “everyone who was in distress, everyone who was in debt, and everyone who was discontented gathered to him. So he became captain over them” (I Samuel 22:2). David later hires himself and his men out to the Philistines as mercenaries, in the Habiru model. The presence and actions of the Habiru are thus consistent with the biblical text, even if they are not proof of an Israelite presence.

The Berlin Pedestal

In our review thus far, we have encountered a number of references in Egyptian records to names that seem to indicate the presence of Israel in Canaan long before Merneptah. Those in the archaeological community who deny the historicity of the conquest, and instead prefer some form of indigenous Canaanite origin for Israel, will look at this as evidence for the existence of distinct groups that would later coalesce into a group known as Israel during the time of Ramesses II. The only way to definitively demonstrate the presence of Israel in Canaan at an earlier date would be to find an earlier mention of that name in Egyptian records. While not universally accepted and of unclear dating, such a reference does exist.

Figure 8: The Berlin Pedestal. Photo © R. Wiskin and P. van der Veen, courtesy of O. Zorn, Berlin Museum

In 1913, Ludwig Borchardt acquired a fragment of a pedestal, or statue base, from an antiquities trader. That fragment is now housed in the Egyptian Museum of Berlin, with catalog number 21687. Unfortunately, we don’t have the accompanying statue, and more importantly, the remaining hieroglyphs do not name the Pharaoh who commissioned it. Absent this, and without clear knowledge of where it was found, the dating of this artifact is open for debate.

Figure 9: The Berlin Pedestal name ring (van der Veen et. al., 2010, p18, translation added)

The pedestal base contains two complete name rings, and most of a third, all indicating Asiatic prisoners. The first name ring reads “Ashkelon”, and the second reads “Canaan”. The third name ring was first proposed to read “Israel” by Manfred Görg. Given that this sequence closely parallels that of the Merneptah stele, it has been suggested that it dates from the Nineteenth Dynasty, from the time of Seti I, Ramesses II, or Merneptah. However, Peter van der Veen, Christoffer Theis, and Manfred Görg, the authors of the key paper of the subject,[26] note that the spellings of all three name rings differ from those of the Merneptah stele. The spellings of both Ashkelon and Canaan match those used in the Eighteenth Dynasty, and specifically during the reign of Amenhotep II.[27] The third name ring is missing its right side, but only one glyph is in question, that on the upper right (See Figure 9). Based on what remains, the authors have proposed the missing glyph to be a vulture, and thus the reading to be i-3-šr-il or “Israel”. This identification of the missing glyph as a vulture was further confirmed by 3D laser scanning and a plastic impression taken in 2011.[28] The reading of Israel thus seems secure, although other readings have been proposed.

If we accept that this name ring does indeed read “Israel”, it brings us back to the question of where to place this record chronologically. The sequence Ashkelon-Canaan-Israel is repeated on the Merneptah stele, and this, combined with a bias toward a Ramesses II date, leads some archaeologists to prefer a date in the Nineteenth Dynasty. However, this cannot account for the spelling differences, which place the origin of this inscription earlier, in the Eighteenth Dynasty. In a later collaboration with Wolfgang Zwickel, van der Veen suggests that spelling differences may derive from archaic versions of the name Israel, or alternatively, from regional accents (see Judges 12:6, for example).[29]

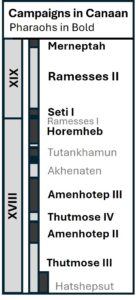

Figure 10: Egyptian campaigns in Canaan

The list of Pharaohs who might have commissioned the Berlin Pedestal is limited to those who campaigned in Canaan. This list includes four consecutive Eighteenth Dynasty Pharaohs from Thutmose III to Amenhotep III, followed by a gap of circa forty years. Canaan campaigns are then attested from the reign of Horemheb to that of Merneptah with the exception of the short reign of Ramesses I (See Figure 10). As previously noted, the spellings indicate a mid-Eighteenth Dynasty origin, particularly in the reign of Amenhotep II. However, in their 2017 article, Zwickel and van der Veen seem hesitant to place it that early, though they suggest it may have been copied from an older list.[30] Based on other evidence that we have reviewed, we can place elements of Israel in Canaan as early as the reign of Amenhotep III. If indeed the pedestal, or the list that it contains, dates from the time of Amenhotep II, it would indicate a defined group known as Israel established in Canaan at the point where our Theory Three places the Exodus, bringing that theory into question. A later date, particularly in the reign of Amenhotep III, would allow an Exodus at the time of Amenhotep II, as proposed in Theory Three, with time enough to wander the wilderness and arrive in Canaan. Either placement would indicate the references to Asher, Reuben, Issachar, and the Shasu of YHWH are references, not to proto-Israelite groups that would later form a unified whole, but to segments of a larger Israel that was already in existence and known to the Egyptians.

At this point, we have exhausted the known Egyptian inscriptions that directly reference Israel or a group that can be linked to or identified as part of that people. This is not, however, the end of the Egyptian evidence. In our quest to place the Exodus Pharaoh, we must consider the place where it all began, the city of Pi-Ramesses, or as it was known previously, Avaris.

Avaris

The archaeological evidence found at Avaris by Manfred Bietak and the Austrian expedition indicates two points in time where a large Semitic population occupied at least part of the city and then disappeared. The eastern suburb of the city was first occupied by a Semitic group in the late Twelfth Dynasty, most likely in the reign of Pharaoh Amenemhat III, whom I and others have identified as the Pharaoh of Joseph.[31] This initial occupation corresponds to stratum H/4 in the eastern suburb of Avaris, and progresses through the following stratum G/4 to G/1 (See Figure 11). At the end of stratum G/1, and in other parts of the city dated to the same period, Bietak identified a number of graves that indicated hasty burials of large numbers of individuals as might be expected to result from a plague or other epidemic. Shortly afterward, the city was abandoned. David Rohl has identified these graves with the Exodus plagues[32] and the subsequent abandonment with the Exodus itself, and the timing aligns with our Theory One.

Figure 11: Detailed stratification of Tell El Dab’a / Avaris. After Kutschera, et. al., 2012, p410, Figure 3. The numbered stars indicate the alignment with three of the theories as to the identity of the Exodus Pharaoh. The area corresponding to the Semitic population is highlighted.

Following the abandonment at the end of stratum G/1 and the hiatus that followed, the eastern suburb was reoccupied by a different Semitic group in stratum F. This second group is what we know as the Hyksos. There were two Hyksos phases, the first is identified by Bietak as the Kingdom of Avaris. It is otherwise known as the Lesser Hyksos. This group would be supplanted by the main Hyksos group, otherwise known as the Greater Hyksos. The Hyksos occupation lasts through stratum E and D until the time of Pharaoh Ahmose I. The archaeological evidence indicates the destruction of the city at this point, followed by a long hiatus. Thus Josephus’ account of the capture of the city by that Pharaoh matches the archaeological evidence. This second departure, forced as it was, provides the archaeological basis for our Theory Two.

Following the departure of the Hyksos, occupation at Avaris continues only in the area known as Ezbet Helmi where a palace was maintained, and later a naval base to support Egyptian forays into Canaan and Lebanon. There is, however, no evidence of a significant Semitic or Asiatic population at Avaris following the expulsion of the Hyksos. For those who prefer Theory Three, this is a significant issue. The archaeological evidence of a Semitic presence that could be associated with the Israelites predates the reign of Thutmose III by circa seventy-five years, and that of Amenhotep II by circa one hundred twenty-five years. It is simply too early to support this Theory. If there was a significant Exodus at that time, those who participated must have come from somewhere else.

Some Conclusions

We have reviewed the various theories as to when the Exodus occurred and which Pharaoh was reigning at that time. In doing so, we have considered both ancient authors and modern opinions. We have also reviewed the Egyptian evidence for Israel’s presence in Canaan and the archaeological evidence from Avaris, the city called Ramesses in Exodus 1:11. In the course of our investigation, we identified four options or theories as to the identity of the Exodus Pharaoh:

Theory One: From Artapanus, our most ancient source, we have the name Kha-nefer-re, which matches Sobekhotep IV of the Thirteenth Dynasty. Artapanus makes him the Pharaoh of the oppression. Josephus identifies another Pharaoh at this time named Timaus in the Greek, whose Egyptian name is Dudimose, also of the Thirteenth Dynasty, and in whose time, “God was averse to [Egypt]”, suggesting the Exodus plagues.

Theory Two: Josephus, however, identifies Ahmose I as the Exodus Pharaoh and associates the Exodus with the expulsion of the Hyksos, or “shepherd kings.” He is followed in this by Africanus and Eusebius

Theory Three: George Syncellus was the first to suggest Thutmose III as the Exodus Pharaoh, aligning Ahmose I with the oppression and choosing this Pharaoh as the one who was ruling eighty years later when Moses returned from exile. Some modern scholars propose this same Pharaoh, or more often his son Amenhotep II, based on counting back four hundred eighty years from Solomon’s reign, following I Kings 6:1

Theory Four: Bishop Ussher, writing in 1650 AD, was the first to suggest Ramesses II as the Pharaoh of the oppression, with the Exodus taking place in the reign of his son; though he incorrectly identifies that son as Amenhotep, not Merneptah. Today, an Exodus in the time of Ramesses II or Merneptah is the dominant theory among archaeologists.

The End of Theory Four

Our review of the Egyptian evidence identified references to four of the tribes of Israel, Asher, Reuben, Issachar, and likely Judah, along with names including a YHWH component, going back as far as the reign of Amenhotep III, as much as one hundred years before the reign of Ramesses II. The Berlin Pedestal provides a reference to Israel that, based on spellings and stylistic grounds, may date even earlier, to the time of Amenhotep II, at least one hundred twenty years before Ramesses II. This leads us to two very significant conclusions:

- The absence of archaeological evidence for an Exodus and conquest in this period is an expected result, given the evidence that Israel was established in Canaan much earlier. In other words, the absence of evidence for a conquest in the time of Ramesses II is explained by the simple fact that the Israelites were already there!

- The evidence of an Israelite presence in Canaan before Ramesses II is fatal to Theory Four. We can safely reject this option.

While we can dismiss this theory based on the evidence so far, we will continue to review the evidence for (or against) it in Part III.

Amenhotep II?

Our review of the evidence at Avaris indicates two events where a large group of Asiatic or Semitic people departed this location. The first precedes the Hyksos period, and the second coincides with the Hyksos expulsion. However, there is no evidence for such a departure later in the Eighteenth Dynasty, in either the time of Thutmose III or Amenhotep II. These Pharaohs reigned for a period from seventy to one hundred fifty years after the departure of the Hyksos. If, in fact, the Berlin Pedestal can be dated to the reign of Amenhotep II, it would create a serious issue for our Theory Three, as it would indicate that Israel was already established in Canaan in his time. Between the lack of evidence for a departure from Avaris and the potential reference to Israel in Canaan at this time, I must say that Theory Three is, at the very least, on shaky ground.

Shepherd Kings?

Our first two theories place the arrival of Israel in Canaan before all of the evidence of their presence there. They are also supported by evidence of a large Asiatic or Semitic group departing from Avaris. Thus, all of the evidence we have reviewed so far is consistent with either theory. While Josephus mistranslated “Hyksos” as “shepherd kings”, as opposed to “rulers of foreign lands”, he still arrived at a plausible theory. On the other hand, what we know of the Hyksos expulsion is not consistent with the biblical account. While the Bible describes a Pharaoh who would not ‘let the people go’, in the case of the Hyksos, the Egyptians were clearly anxious to be rid of them, at least from the information that has been passed down to us. It’s possible that this is propaganda, turning a terrible defeat into an Egyptian victory, but it’s more likely based on the evidence that this event was indeed the expulsion of a hated oppressor.

Dudimose

The inconsistencies between the biblical text and what we know of the Hyksos expulsion bring us back to our Theory One, that of an Exodus during the reign of an obscure Thirteenth Dynasty Pharaoh by the name of Dudimose. Like the Hyksos theory, this predates any evidence of Israel in Canaan and is supported by the evidence at Avaris. The quote of Manetho provided by Josephus that “God was averse” to the Egyptians at this time, and the plague pits found at Avaris associated with the departure of a Semitic group at the end of stratum G/1 both hint at the Exodus plagues. The primary objection to this theory is simply that it seems too early based on our modern focus on Ramesses II and Amenhotep II and the timespan given in I Kings 6:1.

As we conclude Part II, we are left with three theories as to who was the Pharaoh of the Exodus, and more importantly, when it occurred. In Part III, we will turn our attention to the archaeological evidence for the conquest to see if we can reach a clearer conclusion.

The Exodus Pharaoh Part III – The Conquest ->

Footnotes

[1] See for example, Rohl (2015), Kitchen (2003)

[2] The Stele of Reniseneb (or Resseneb) indicates that Ankhu was still active into the reign of Sobekhotep I in the early Thirteenth Dynasty. If Ankhu is Joseph, then Reniseneb is Manasseh.

[3] Grajetzki (2024), p83-84

[4] There are perhaps two Pharaohs of this name who ruled consecutively, or one who changed his pre-nomen during his reign. We have stele attesting to both names. We do not have any statuary that I’m aware of. For the identification of Timaus with Dudimose, see Redford (1992), p104; Rohl (1995), p280-82; Rohl (2015), p149

[5] See Redford (1992), p101-06

[6] See Bietak (2013) and Rohl (2007), p199 and 222

[7] At different times the Pharaohs of the Theban dynasties maintained a summer residence at Avaris. It’s not clear if this was the case in the Thirteenth Dynasty as it was in the Twelfth. It’s also possible that Moses was dealing with a Thirteenth Dynasty Pharaoh based at Avaris after central authority disintegrated, and not with a Hyksos Pharaoh.

[8] Redford (1992), p108 and Note 54

[9] Pritchard (1969), p231. Translation of Papyrus Sallier I, logged as British Museum 10185

[10] See Redford (1992), p117-18

[11] Burke (2008) provides an extensive discussion on Middle Bronze Age fortified cities in Canaan.

[12] Breasted (1906), Vol II, p125-6, §303

[13] Pritchard (1969), p234.

[14] See Judges 3:8. Cushan-Rishathaim is king of Naharin in the Hebrew, generally translated as Mesopotamia. The kingdom of Naharin or Mitanni occupied the area between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what is today northern Syria, northern Iraq, and eastern Turkey.

[15] Breasted (1906), Vol II, p170, §402

[16] Pritchard (1969), ANET, p247, quoting the Memphis and Karnak Stelae of Amenhotep II. The actual total is 101,128. The difference may be that 89,600 is only the men or only the adults.

[17] Finkelstein (1996) estimates a settled population (i.e., not including nomadic groups like the Shasu) of Canaan in the Late Bronze Age at approximately 90,000.

[18] van der Veen (2022)

[19] The inscription is cataloged in Simons (1937), p 61-63 and p 147. The diagram of the temple on p 62 is incorrect with respect to both the shape of the rock-cut room and the location of the inscription, which is actually on the right wall at the back corner.

[20] See Simons (1937), p 126, Note 10.

[21] van der Veen (2022)

[22] Ya-huwa = “Ya makes to exist”, or in other words, I AM. Thanks to David Rohl for the translation.

[23] Van der Veen (2022), p 30

[24] Ibid, p 31-32

[25] Rohl (1995), p 205

[26] van der Veen, Theis, and Görg (2010). See this article for a detailed discussion of how the middle line is read “šr”

[27] Spelling variances are common in ancient texts, particularly when dealing with foreign names, which must be spelled phonetically. I should note that American English spellings were not standardized until the early nineteenth century, notably through Webster’s Dictionary.

[28] van der Veen (2012).

[29] Zwickel and van der Veen, 2017

[30] Ibid, p 131.

[31] See www.thebiblicaltimeline.org/articles-videos/joseph/. David Rohl also makes this identification in his books. Doug Petrovich prefers the previous Pharaoh, Senusret (Sesostris) III.

[32] Rohl (2015), p 153-54

References

The following is a list of the works referenced above

Bietak, M. (2013). The Impact of Minoan Art on Egypt and the Levant – A Glimpse on Palatial Art from the Naval Base of Peru-nefer at Avaris. In J. Aruz (Ed.), Cultures in Contact: From Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C. The MMS Symposia (pp. 188-198). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Bimson, J. J. (2025). An Alternative Paradigm for Israel’s Origins in Canaan. In P. G. van der Veen, R. Wallenfels, & P. James (Eds.), Assyria and the West (pp. 167-204). Bicester, United Kingdom: Archaeopress.

Breasted, J. H. (1906). Ancient Records of Egypt. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Burke, A. A. (2008). Walled Up to Heaven: The Evolution of Middle Bronze Age Fortification Strategies in the Levant. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

Finkelstein, I. (1996). The Territorial-Political System of Canaan in the Late Bronze Age. Ugarit-Forschungen, 28, 221-255.

Grajetzki, W. (2024). The Middle Kingdom of Ancient Egypt (2nd ed.). London; New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Josephus, F. (1999). The Complete Works of Josephus. (P. L. Maier, Ed., & W. Whiston, Trans.) Grand Rapids, Michigan: Kregel Publications.

Kitchen, K. A. (2003). On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans.

Pritchard, J. B. (1969). Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Redford, D. (1992). Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Rohl, D. M. (1995). A Test of Time: The Bible – From Myth to History. London: Century.

Rohl, D. M. (2007). The Lords of Avaris. London: Arrow Books.

Rohl, D. M. (2015). Exodus: Myth or History? St.. Louis Park, Minnesota: Thinking Man Media.

Simons, J. (1937). Handbook for the Study of Egyptian Topographical Lists Relating to Western Asia. Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill.

van der Veen, P., Theis, C., & Görg, M. (2010). Israel in Canaan (Long) Before Pharaoh Merenptah? Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections, 2(4), 15-25.

van der Veen, P. (2012). Berlin Statue Pedestal Reliefs 21687 and 21688: Ongoing Research. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections, 4(4), 41-42.

van der Veen, P. G. (2022). Israel and the Tribes of Asher, Reuben and Issachar: An Investigation into Four Canaanite Toponyms from New Kingdom Egypt. In S. J. Wimmer, & W. Zwickel (Eds.), Ägypten und Altes Testament (pp. 25-36). Münster: Zaphon.

Zwickel, W., & van der Veen, P. (2017). The Earliest Reference to Israel and Its Possible Archaeological and Historical Background. Vetus Testamentum, 67, 129-140. doi:10.1163/15685330-12341266