The Exodus Pharaoh: Part I – The Candidates

Photo: Ramesses II from his temple at Abu Simbel (Photo: © Talbot Smith)

There is perhaps no more important question in biblical chronology than the identity of the Pharaoh at the time of the Exodus. Answering this question would firmly anchor the timeline of the Bible to that of Egypt. It would also allow us to better evaluate the archaeological evidence for the Exodus and the conquest. Unfortunately, the Bible is silent on the identity of Moses’ adversary and offers only a few clues that we might use in our attempt to solve this mystery. Come with me as we explore the evidence, from ancient texts to recent archaeological finds, to get some perspective on this question.

The Exodus Pharaoh, Part I: The Candidates

The title “Pharaoh” is used seventy-two times in Genesis and over one hundred times in Exodus, in the context of Abram, Jacob, Joseph, and Moses, yet at no point are any of these Pharaohs given a name. Only beginning in the book of Kings, in the period of the divided monarchy, does the Bible begin to provide the names (or nicknames) of the Pharaohs.[1] This is, of course, very frustrating to those of us wishing to place the events of the Exodus and conquest firmly against the backdrop of history. Who were these Pharaohs, and in particular, who was the Pharaoh of the Exodus account?

Setting the Boundaries

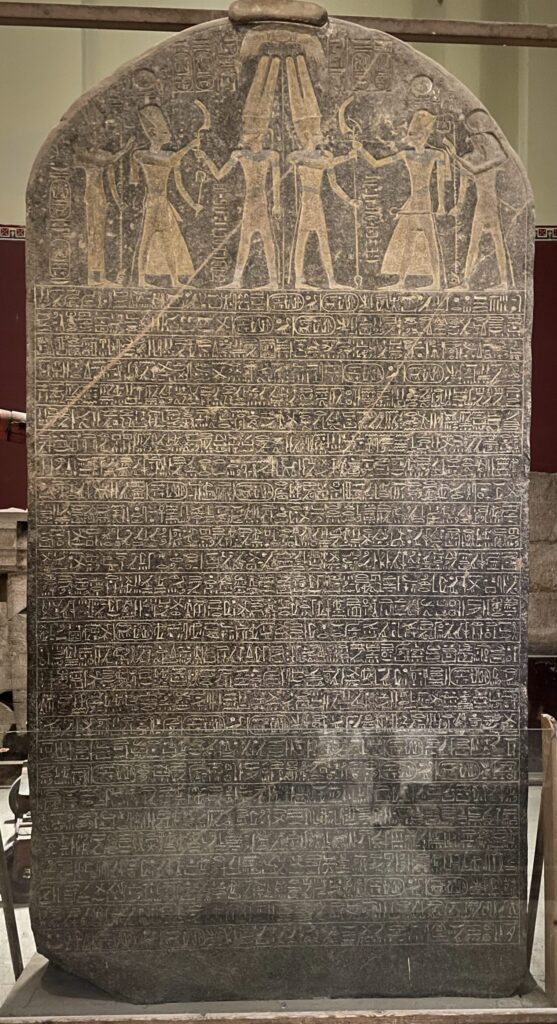

Much of the search for the Pharaoh of the Exodus revolves around places and dates, and before we begin, we should set some reasonable boundaries in terms of where to look for this individual in Egyptian history. The latest possible date for the conquest of Canaan is the reign of the Pharaoh Merneptah, son and successor of Ramesses the Great (Ramesses II). He commissioned the Merneptah or Israel Stele, which records the following lines:

Figure 1: The Merneptah Stele in the Old Cairo Museum, 2024. (Photo: Talbot Smith)

“The princes are prostrate, saying ‘Peace!’

Not one raises his head among the Nine Bows. [The traditional enemies of Egypt]

Desolation is for Tjehenu [Libya];

Hatti [the Hittites] is pacified;

Plundered is the Canaan with every evil;

Carried off is Ashkelon;

Seized upon is Gezer;

Yanoam is made non-existent;

Israel is laid waste—its seed is no more;

Kharru has become a widow because of Egypt.

All lands together are pacified.

Everyone who was restless has been bound”[2]

This passage indicates that a people known as “Israel” was already in Canaan in the time of this Pharaoh. Thus, if we allocate time for the wanderings in the wilderness, the terminus ante quem, or latest possible date for the Exodus, falls in the long reign of Ramesses II.

To establish the earliest possible date for the Exodus, we should consider Exodus 1:11 :

Therefore they set taskmasters over them to afflict them with their burdens. And they built for Pharaoh supply cities, Pithom and Raamses (NKJV)

Cities are often built and then rebuilt, remodeled, and expanded over a long period of time, and it’s not clear from this passage if we are talking about the founding of these cities or an expansion, but certainly, the Exodus could not have occurred before these cities existed.

The city of Raamses, or more correctly, Pi-Ramesses, was indeed constructed by Ramesses II and has been definitively located at Tell el-Dab’a in the Nile Delta. However, this city was built on top of a much older city, the city of Avaris, whose origins date back to Middle Kingdom times, at least to the time of Joseph.[3] We will come back to Avaris in Part II, but in the immediate context, the history of this site does not provide any help in narrowing our search, so we must look instead at Pithom.

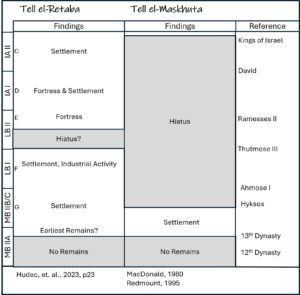

Figure 2: Archaeological stratification at the two candidate sites for Pithom

Pithom is generally believed to be a corruption of the Egyptian Pi-Atum, or the house (temple) of Atum. Several inscriptions naming this place have been found in the Wadi Tumilat in Egypt, but there remains an active debate as to its identity. The debate focuses on two sites, Tell el-Retaba and Tell el-Maskhuta, with eminent Egyptologists on both sides of the debate. To some extent, where scholars fall in this debate depends on their preconceptions about when the Exodus took place or when the Exodus account was written; thus, it may be best to look at them collectively as opposed to focusing on a single site. The stratification of the two sites is shown in Figure 2, and their locations are shown in Figure 3. We are not going to settle the question of which site is biblical Pithom here (the debate has been raging for over 100 years), but given there is almost continuous occupation at Tell el-Retaba these sites could provide us with an earliest possible date for the Exodus, or what archaeologists call a terminus post quem. As noted above, the construction described in the Exodus account need not be the initial construction at the site and could have been a later expansion. The latest excavation reports for Tell el-Retaba identify the earliest settlement in Stratum G at the beginning of the Middle Bronze IIB period associated with the arrival of the Hyksos. The pottery in these early layers corresponds to Hyksos layers at other sites in Egypt. In the latest report from the site, the excavators note:

“Notably, for the first time, scattered pottery sherds were discovered, indicating that occupation in Tell el-Retaba may reach back to the Middle Kingdom [MB IIA], although specific archaeological structures associated with this material have not been identified yet.”[4]

Figure 3: Cities of the Nile delta showing the potential locations of Pithom

On this tentative evidence, I will place the beginnings of Tell el-Retaba at the end of the MB IIA period. At Tell el-Maskhuta, the earliest finds are Asiatic burials from the same MB IIA period, while the pottery is of a transitional MB IIA/B and MB IIB type.[5] There is, however, an absence of MB IIC pottery, indicating the site was abandoned before the Hyksos expulsion. This abandonment would continue well into the Egyptian Third Intermediate period, or until nearly the time of Josiah. However, this is not an issue for those who wish to argue that the Exodus account was only composed at that time or even later. The important thing is that both sites seem to begin at the same time: at the very end of Middle Bronze IIA or in the transition from MB IIA to MB IIB. Consequently, it does not matter which is the correct site for our purposes, as both yield approximately the same earliest possible date for the Exodus. In Egyptian terms, this earliest date corresponds to the late Thirteenth Dynasty, the end of the Middle Kingdom, and the beginning of the Hyksos period.

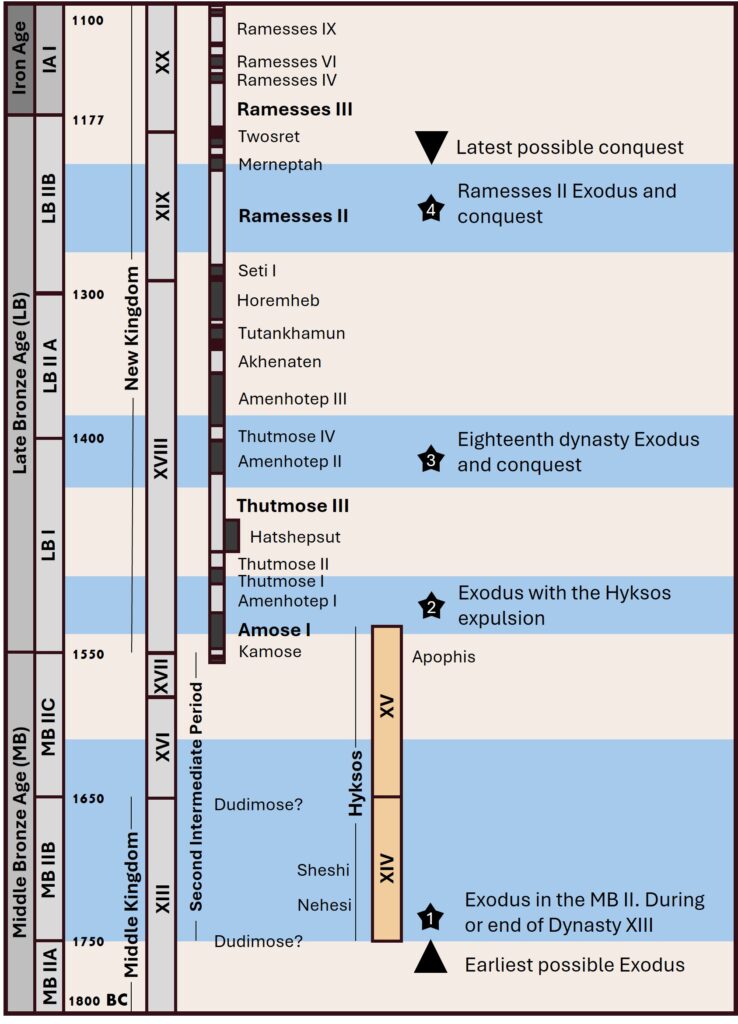

With these earliest and latest dates in place, we can now turn our attention to identifying potential candidates for the Pharaohs involved in the Exodus story, either in oppressing the Israelites or as the Pharaoh who endured the plagues and ultimately perished in the Red Sea.

Four Theories

The first to write any sort of history of Egypt was Herodotus, often called the father of history. Herodotus wrote around 450-425 BC, in the period after the Persian wars against Greece[6], and a hundred years before the Greek conquest of Persia and Egypt under Alexander the Great. His work, The Histories, is a mixture of facts and tall tales covering much of the ancient world. He gives some highlights of the Old Kingdom, including the building of the pyramids, and then seems to move directly to the Third Intermediate Period, and the last days of Egypt before it became a province of Persia. Unfortunately, in doing so, he skips over the period that we are most interested in. He did make quite an impression on the Egyptians, however, as our next writer found it necessary to write a book titled Against Herodotus (sadly not preserved), to correct his errors.

In the first half of the third century BC (290-260 BC), in the reign of either Ptolemy I or Ptolemy II, an Egyptian priest known as Manetho wrote Aegyptiaca, a history of Egypt in Greek, in three volumes. It was Manetho who introduced the world to the concept of Egyptian dynasties that we still use today. Unfortunately, Manetho’s history is now lost, but it was available to other ancient writers at least to the time of Eusebius, and fragments of Manetho are preserved in direct quotations from Eusebius, Josephus, and Africanus. Manetho’s history does not always match our modern understanding of Egyptian history, but his work remains a useful reference today, even as it was 2000 years ago. While Manetho does not directly identify the Exodus in his history, he records events that could be associated with the Exodus story, and he was a key source used by Josephus and the early church fathers in their quest to identify the Pharaoh of the Exodus.

The Ancient Historians |

|||

| Historian | Wrote | Contributions | |

| Herodotus | c 450-425 BC | The Father of History. First to write a history of the ancient world. Documented many aspects of the culture as well. | |

| Manetho | c 290-260 BC | Egyptian priest. Wrote Aegyptica, a history of ancient Egypt which survives only in fragments in later authors, notably Josephus, Africanus, and Eusebius | |

| Artapanus | > 250 BC, < 100 BC |

Jewish historian from Alexandria, Egypt. Wrote a history of the Jewish people in Greek titled Concerning the Jews. Only a few fragments survive. | |

| Flavius Josephus | c 75-95 AD | Jewish historian. Wrote Antiquities of the Jews, a history from creation to his time, The Jewish War, describing the Great Jewish Revolt of 69-70 AD, and Against Apion, a defense of his other works. | |

| Sextus Julius Africanus | c 200-240 AD | Christian historian. Wrote Chronographiai, a five-volume history of the world from creation to his time, which survives only in fragments quoted by other authors | |

| Eusebius of Caesarea | c 300-339 AD | Bishop of Caesarea. Best known for his history of the early church, he also produced the Onomasticon, identifying and locating many biblical places, and the Chronicle, a parallel history of the civilizations of the ancient world. | |

| George Syncellus | c 800 AD | Byzantine monk and author of Extract of Chronography, a history of the world after the approach of Africanus and Eusebius | |

| Table 1 | |||

Manetho was followed by Artapanus, a Jew from Alexandria, Egypt, who wrote a history of the Jewish people. His work does not survive except for a few fragments in Eusebius and Clement of Alexandria. However, Artapanus is the earliest source to recount the Exodus story while naming a Pharaoh involved. Eusebius records that:

“Artapanus says in his work about the Jews that … ‘[Pharaoh] had a daughter named Merrin, whom he was engaged to a certain Kenefre, who ruled over the lands around Memphis. At that time, many were ruling in Egypt. This daughter was said to have given birth to a child by one of the Jews, and this child was named Moses.'” (Preparation for the Gospel, Book 9:27.1-3)

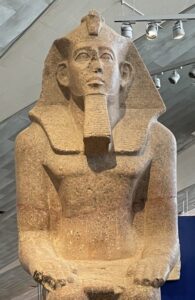

Figure 4: Kha-nefer-re Sobekhotep IV, Grand Egyptian Museum, Cairo, 2025 (Photo: Talbot Smith)

The comment that “many were ruling in Egypt” is interesting because, as we will see, this would place the birth of Moses in a time where central rule had broken down in Egypt, a time we know as the Second Intermediate Period (SIP). Clement relates that Moses was briefly imprisoned by Pharaoh:

“And so Artapanus, in his work On the Jews, relates ‘that Moses, being shut up in custody by Chenephres, king of the Egyptians, on account of the people demanding to be let go from Egypt, the prison being opened by night, by the interposition of God, went forth …'” (Stromata, Book 1:23:154)

Now Kenefre and Chenephres are just different spellings of the same name, which in Egyptian is rendered as Kha-nefer-re. David Rohl notes that there was only one Pharaoh in all of Egyptian history with this coronation name: Sobekhotep IV, who was perhaps the most powerful pharaoh of the Thirteenth Dynasty, the dynasty ruling before and likely in the early part of the Second Intermediate Period.[7] The two passages I have quoted place this Pharaoh at different points in the story. In the first, he is a Pharaoh of the oppression (the oppression spanning at least the first eighty years of Moses’ life, it certainly involved more than one Pharaoh),[8] and in the second of the Exodus. Both cannot be correct, and based on other references in Eusebius, Sobekhotep IV must be associated with the oppression. The context of the reference in Clement may indicate that Moses was imprisoned after killing the Egyptian and before escaping to Midian. Regardless, this name suggests a link to the Thirteenth Dynasty and an Exodus at the earliest part of what we would consider a potential range (see Figure 11).

Josephus provides an interesting quote from Manetho as an explanation of how Egypt came to be invaded by outsiders known as the Hyksos:

“There was a king of ours whose name was Timaus. Under him it came to pass, I know not how, that God was averse to us, and there came, after a surprising manner, men of ignoble birth out of the eastern parts, and had boldness enough to make an expedition into our country, and with ease subdued it by force, yet without our hazarding a battle with them.” (Against Apion, I 14:75)

Of note is the fact that “God” is in the singular as opposed to the plural “gods” found in the same passage. Josephus seemingly missed the importance of this passage to our quest, placing the Exodus later (as we shall see shortly). However, this event apparently left Egypt powerless to defend against an invasion from Canaan, and we should consider the possibility that “God was averse” is a reference to the destruction of Egypt by the Exodus plagues. Note that if Sobekhotep IV is a Pharaoh of the oppression, then Timaus, generally associated with the Pharaoh Dudimose, in whose time God was averse to the Egyptians, can be the Pharaoh of the Exodus. This early dating provides our first theory as to the Exodus Pharaoh:

Theory One: The Exodus occurred in the Thirteenth Dynasty, just before or early in the Hyksos period, with Sobekhotep IV as the Pharaoh of the oppression and Dudimose as the Pharaoh of the Exodus.

This theory is primarily advocated by supporters of revised chronologies such as David Rohl and Peter James.[9] However, if you are willing to look at the four hundred eighty year period given in I King 6:1 as symbolic this option could be considered without a revised chronology.

Flavius Josephus, writing in the first century AD, is our source for the quote from Manetho regarding how, in the time of Timaus, or Dudimose, “God was averse to us”. However, Josephus’ reason for mentioning this event is not to align it with the Exodus, but to relate the circumstances of the conquest of Egypt by the Hyksos. In his Antiquities of the Jews, he does not mention the name of a Pharaoh as he recounts the Exodus story. However, he discusses Manetho’s account of the Exodus at length in another work, Against Apion, and associates the Exodus with the Hyksos expulsion. Today, we translate the term “Hyksos” as “rulers of foreign lands”, but Josephus translates that term as “Shepherd Kings” or “Captive Shepherds” and sees in that term the Israelites[10]. He then proceeds to describe their departure from Egypt:

[Quoting Manetho] “These people, whom we have before named kings, and called shepherds also, and their descendants,” as he says, “kept possession of Egypt five hundred and eleven years.” After these, he says, “That the kings of Thebais [Thebes, i.e., the Seventeenth Dynasty] and the other parts of Egypt made an insurrection against the shepherds, and that there a terrible and long war was made between them.” He says further, “That under a king, whose name was Alisphragmuthosis [Kamose], the shepherds were subdued by him, and were indeed driven out of other parts of Egypt, but were shut up in a place that contained ten thousand acres; this place was named Avaris.” Manetho says, “That the shepherds built a wall round all this place, which was a large and a strong wall, and this in order to keep all their possessions and their prey within a place of strength, but that Thummosis the son [brother] of Alisphragmuthosis made an attempt to take them by force and by siege, with four hundred and eighty thousand men to lie rotund about them, but that, upon his despair of taking the place by that siege, they came to a composition with them, that they should leave Egypt, and go, without any harm to be done to them, whithersoever they would; and that, after this composition was made, they went away with their whole families and effects, not fewer in number than two hundred and forty thousand, and took their journey from Egypt, through the wilderness, for Syria; but that as they were in fear of the Assyrians, who had then the dominion over Asia, they built a city in that country which is now called Judea, and that large enough to contain this great number of men, and called it Jerusalem.” (Against Apion, 1:14)

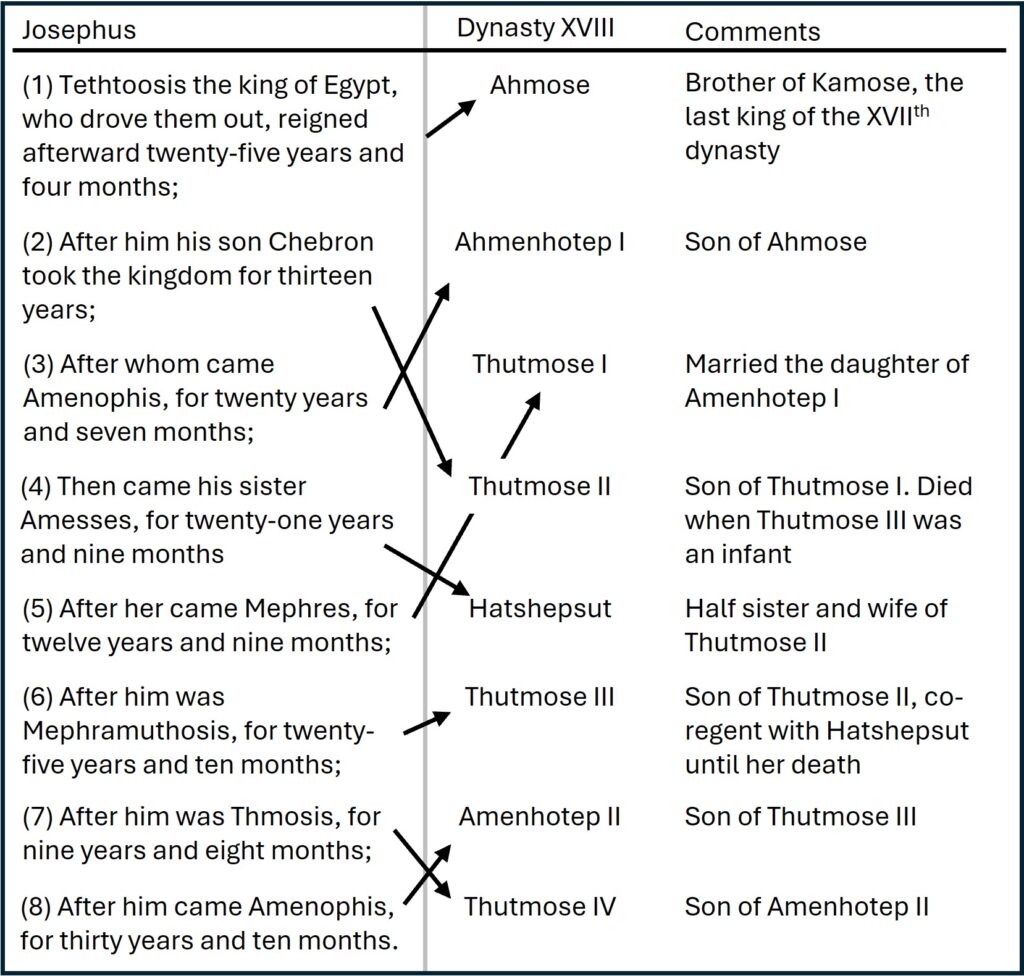

The Exodus then would be synonymous with the Hyksos expulsion, which he credits to a king “Thummosis” or “Tethtoosis”, which certainly looks like a corruption of Thutmose. There were four Pharaohs named Thutmose in the Eighteenth Dynasty, but as he lists the subsequent Pharaohs and their reigns, it becomes clear that this Tethtoosis can only be Ahmose, who we now understand to be the founder of that dynasty, and the Pharaoh responsible for driving the Hyksos out of Egypt. The list of Pharaohs quoted from Manetho by Josephus is a bit jumbled, but I believe that we can untangle it as shown in Figure 5. The first column shows the sequence as given by Josephus from Manetho, and the second column shows the correct sequence developed from archaeological finds and other textual sources. Arrows indicate how the two relate. As a general observation, Josephus’ list is a bit out of order as compared to our current understanding of the sequence of these Pharaohs, but the reign lengths that he records are approximately correct. What is most important to take away from this list is that “Tethtoosis” is the first ruler of this dynasty and therefore should be equated with Ahmose I, and not with any of the later Pharaohs we know as Thutmose.

Figure 5: The Beginning of the Eighteenth Dynasty according to Josephus and modern archaeology

Figure 6: Second Stele of Kamose, Luxor Museum, 2024 (Photo: Talbot Smith)

In addition to Manetho’s account, we have two steles from Pharaoh Kamose that record his war against the Hyksos, but Kamose was ultimately unable to conquer Avaris. The destruction of Avaris is recorded in the tomb inscription of one Ah-mose, son of Eben, describing his service under Ahmose I:

“Then Avaris was despoiled. Then I carried off spoil from there: one man, three women, a total of four persons. Then his majesty gave them to me to be slaves.”[11]

Ah-mose also records accompanying Ahmose I for a three-year siege of the Hyksos stronghold of Sharuhen in southwestern Canaan. The conclusion then is that, if some part of the population of Avaris was paroled to Canaan, others remained until the city fell, and those that did go to Canaan did not live in peace for long.

The account as given in Manetho portrays the departure of the Hyksos for Canaan as a military victory on the part of the Egyptians, and this is substantiated by the archaeological finds. This is, of course, far from the account given in the Bible, which ends in an Egyptian defeat. However, given the tendency of the Egyptian reports to be propagandistic, always glorifying Pharaoh, we should not dismiss the possibility that these events do relate to the Exodus. At least not without further investigation.

Following his discussion of the Hyksos expulsion, Josephus continues with a passage directed at refuting Manetho’s account of the origin of the Israelites and their departure from Egypt.[12] To briefly paraphrase, Manetho recounts that a Pharaoh by the name of Amenophis (i.e., one of the Amenhoteps) received an oracle that he must remove the diseased and maimed people from Egypt. Rather than drive them out, he collects them and places them in the city of Avaris, which at this point has been abandoned by the Hyksos, the same city that would later take the name Ramesses. Once gathered together, this group elects as their leader a priest from Heliopolis who subsequently changes his name to Moses. Following a long war, in which Moses solicits support from the Hyksos enclave in Jerusalem, Moses and his followers are driven out of Egypt to Canaan. Josephus rejects this story as an anti-Semitic tale promulgated by the Egyptians. Notably, he states the following:

“It now remains that I debate with Manetho about Moses. Now the Egyptians acknowledge him to have been a wonderful and a divine person; nay, they would willingly lay claim to him themselves, though after a most abusive and incredible manner, and pretend that he was of Heliopolis, and one of the priests of that place, and was ejected out of it among the rest, on account of his leprosy; although it had been demonstrated out of their records that he lived five hundred and eighteen years earlier, and then brought our forefathers out of Egypt into the country that is now inhabited by us.” (Against Apion, Book I 31.279-280)

Josephus’ position is that Manetho’s story is a fabrication, and he goes so far as to call it a lie. This story is also placed, by Josephus’ calculations, over five hundred years after the actual Exodus, although all of the Pharaohs named Amenhotep reigned in the Eighteenth Dynasty, or within about a hundred years of where Josephus places the Exodus. Nonetheless, we will find Amenhotep, at the correct time, in one of our other theories.

About a hundred years after Josephus, we have the Christian historian Sextus Julius Africanus. His history, called Chronographiai, does not survive except, similar to Manetho, in fragments and excerpts in the works of later authors such as Eusebius and George Syncellus. Africanus clearly associated the Exodus with the Hyksos expulsion, and with Ahmose, the first Pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty. He is the first to try and put a date on the Exodus and gives a period of 1,020 years from the Exodus to the first Olympiad (776 BC), placing the Exodus in 1796 BC. However, in doing so, he calculates a total of 719 years from the Exodus to the fourth year of Solomon.[13] Interestingly enough, if we correct this total to 480 years to match I Kings 6:1, we would place the Exodus in 1557 BC, exactly where modern chronologies place Pharaoh Ahmose and the Hyksos expulsion. Africanus also writes:

“Polemo, for instance, in the first book of his Greek History says: In the time of Apis, son of Phoroneus, a division of the army of the Egyptians left Egypt, and settled in the Palestine called Syrian, not far from Arabia: these are evidently those who were with Moses. And Apion[14] the son of Poseidonius, the most laborious of grammarians, in his book Against the Jews, and in the fourth book of his History, says that in the time of Inachus, king of Argos, when Amosis [Ahmose]reigned over Egypt, the Jews revolted under the leadership of Moses.” (as preserved in George Syncellus Chronographia)[15]

Figure 7: Ahmose I, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Public Domain

Africanus is thus in the same camp as Josephus, placing the Exodus at the time of the Hyksos expulsion under Ahmose. Josephus and Africanus thus give us our second theory:

Theory Two: The Exodus coincides with the expulsion of the Hyksos from Egypt under Ahmose, the first Pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty.

The next writer to address this subject was Eusebius of Caesarea, who wrote his Chronicle around 325 AD. He also references the timing of the Exodus, with quotes from Africanus, in his Preparation for the Gospel. Eusebius relied heavily on Manetho, as Josephus did, and is one of our sources for fragments of that work. He also quotes Josephus and many other sources that are now lost to us. Eusebius provides much the same list of the Eighteenth Dynasty Pharaohs as Josephus, although he names the first Pharaoh as “Amosis” in agreement with Africanus. He notes that:

“[Ptolemy the Mendisian] wrote about the actions of the Egyptian kings in three complete books. He says that Amosis was the king of Egypt when Moses led the Jews out of Egypt …” (Preparation for the Gospel, Book 10:12.4)

However, in the list of Eighteenth Dynasty Pharaohs in his Chronicle, Eusebius includes the following note:

“Achencherses [Akenaten], 16 years. In his reign, Moses as general of the Jews, took them out of Egypt.” (Chronicle, 50)

Figure 5 shows the first eight Pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty, and Akenaten was the tenth in that line. Unfortunately, Eusebius does not offer any evidence or argument to support this, and as just noted, it is inconsistent with his statements elsewhere. Syncellus, in his discussion of Eusebius’ chronology, goes so far as to say:

“He contradicts the opinions of so many learned men, and introduces his own commentary, which is not supported by any ancient testimony.”[16]

I suspect this alignment is coincidental and stems from his parallel timelines of Israel and Egypt. If so, it indicates that Eusebius’ Egyptian timeline includes about 200 extra years to this point. Syncellus notes this discrepancy:

“It has been found that Eusebius erred in correctly designating the age of Moses by at least two hundred years.”[17]

How exactly Eusebius reached this alignment is unclear, though Syncellus makes the comment that, “[Eusebius] has sinned by following the diminished path of counting years.”[18], presumably in contrast to following more ancient writers. What is most interesting is that Eusebius’ placement of the Exodus at the time of Akenaten in his Chronicle stands in opposition to his placement of the Exodus at the time of Ahmose in Preparation for the Gospel. Consequently, I will align Eusebius with our Theory Two, and, on the advice of Syncellus, dismiss the Akenaten option. As we will see in Part II, an Exodus under Akenaten would be too late based on the archaeological evidence.

The final ancient historian that we shall consider is George Syncellus, a Byzantine monk who wrote circa 800-810 AD[19]. His great work was Chronographia, a history of the world to that time. Syncellus reviews many of the earlier writers on this subject, including extensive quotes from Africanus and Eusebius and commentary on those authors, Josephus, and others. Syncellus is a significant source of fragments from many writers whose works have been lost, notably Africanus, including many that I have already quoted. However, Syncellus ultimately does not agree with our previous three writers in placing the Exodus in the time of Ahmose, at the beginning of the Eighteenth Dynasty.

Figure 8: Thutmose III, Luxor Museum, 2024 (Photo: Talbot Smith)

Syncellus places the Exodus in the time of a Pharaoh that Manetho calls “Misphragmouthosis”, however, we know him today as Thutmose III. To my knowledge, Syncellus is the earliest author to make this association. While it is possible that he takes this from someone earlier, he does not provide a reference. Today, proponents of an Exodus in the time of Thutmose III or his son Amenhotep II arrive at this date by following I Kings 6:1 and deducting 480 years from the reign of Solomon. Syncellus reaches this conclusion via different logic:

“This was indeed our intention, that we should show that Moses was born in the time of Amos, who is also Tethmose, the son of the first king of the eighteenth dynasty of Aseth, if we assign thirty years to Amos, and sixteen years to Aseth his father; but according to several and more correct versions, if we grant 20 years to this Aseth, and then 26 to Amos, the day of Moses’ birth will be found in the 17th or 16th year of Aseth himself (this calculation was made by us with the most accurate skill we could)”[20]

Syncellus retains the association of Ahmose with the Exodus story, but rather than place the departure from Egypt in his time as other authors did, he places Moses’ birth with Ahmose or late in the reign of his father, one “Aseth”. Ahmose was in fact preceded by his brother Kamose, who was preceded by their father, Seqenenre Tao, who is perhaps the Aseth of this passage. The Exodus occurs when Moses is eighty years old, and so Syncellus’ logic is as follows:

“I think that Africanus was unaware of the same man, who is called Amos, also Ahmose, and also Tethmosis, who was the son of Aseth, (as will be shown in what follows) and Misphragmouthosis, the sixth numbered by him, who is also distinguished by the name of Amosis. Certainly under Amos the first of that name, the Amos of Africanus, or certainly four years before his reign, Moses, as is certainly clear from what has been said, came to light; … but under Amos the second of the same name, who also had the name of Misphragmouthosis, he went out of Egypt with the whole company of the people: he went out, … at the proper age of eighty.”[21]

Syncellus, of course, makes Thutmose III the Exodus Pharaoh. As we will see shortly, later writers, who arrive at this solution based on completely different logic, make Thutmose III the Pharaoh of the oppression and his son Amenhotep II the Pharaoh of the Exodus. For our purposes, however, either option would have us look in the same archaeological period, and I will include this variation as part of Theory Three.

Theory Three: The Exodus took place in the middle of the Eighteenth Dynasty, with Pharaoh Thutmose III as either the Pharaoh of the oppression or the Exodus

Figure 9: Amenhotep II, Grand Egyptian Museum, Cairo, 2025 (Photo: Talbot Smith)

Josephus, Africanus, Eusebius, and Syncellus all placed the Exodus in the first half of the Eighteenth Dynasty, with either Ahmose or Thutmose III as the Pharaoh associated with that event. Interestingly, these authors were all aware of the name Ramesses as they record it in their kings lists, but none of them associate him with the Exodus. All of these sources tie the Exodus to events in Egyptian history recorded by Manetho and others. Only Eusebius seems to attempt to identify the Exodus Pharaoh using dates, and in doing so, gets a result which is inconsistent with the others and with his other writings. As far as I can tell, none of the ancient sources suggest Ramesses II as the Exodus Pharaoh. In general, we ignore the early church fathers at our peril, and that seems to be the case here. To find the first suggestion of Ramesses II’s involvement in the Exodus, we must move forward another 850 years to the beginning of the modern era.

In 1650 AD, Bishop James Ussher published his Annals of the World, a history of world events by year from creation to his time. Ussher identifies Ramesses II as the Pharaoh of the oppression and his son, Amenophis (Amenhotep) as the Pharaoh of the Exodus.[22] He writes:

“172 Ramesses Miamun [Ramesses II] died in the sixty-seventh year of his reign about 1511 BC or 3203 JP.[23] The length of his tyrannical reign seems to be noted in these words:

‘And it came to pass in process of time, that the king of Egypt died, and the children of Israel sighed by reason of the bondage, and they cried …’ [Exodus 2:23]

173a This was the cruel bondage which, even after Ramesses was dead, they endured for about a further nineteen years and six months under his son Amenophis, who succeeded him.” (Annals of the World, Third Age, 172-173)

This places the Exodus in 1492 BC (1511 – 19 years) by Ussher’s reckoning. In this same passage he provides an additional note:

“173b Amenophis was the father of Sethosis or Ramesses who was the first king of the following dynasty, or successive principality, which Manetho makes to be the nineteenth dynasty. (This was not under the other Amenophis who was the third king in the eighteenth dynasty as Josephus vainly surmised.) It was the time of the second Amenophis in the eighteenth dynasty that the Israelites left Egypt, under the conduct of Moses , according to Manetho’s account.” (Annals of the World, Third Age, 173)

Figure 10: Ramesses II, Grand Egyptian Museum, Cairo, 2025 (Photo: Talbot Smith)

But wait, isn’t Ramesses II a king of the Nineteenth Dynasty, and Amenhotep II a king of the Eighteenth Dynasty? Ussher is relying on the fragments of Manetho preserved in earlier writers, and in particular, I suspect, Eusebius. The dynastic list in Eusebius’ Chronicle includes the sequence Ramesses for sixty-six or sixty-seven years followed by Amenophis for forty years, both at the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty and again at the beginning of the Nineteenth Dynasty, following Sethosis / Seti I as the founder of that dynasty. Neither list includes Merneptah.[24] As we have seen earlier in this chapter, Manetho’s list, at least as passed down to us, is out of order for the Eighteenth Dynasty, and here we have the additional problem of Ramesses II (based on the reign length) and an Amenophis duplicated at the end of dynasty eighteen and the beginning of dynasty nineteen. The Nineteenth Dynasty, in fact, begins with the short reign of Ramesses I, followed by Seti I and then the long reign of Ramesses II. The appearance of these two Ramesses in close proximity may be the source of the confusion.

Based on this passage, Ussher can be seen as supporting a variant of our Theory Three, with Amenhotep as the Exodus Pharaoh, while also introducing a new theory for the first time:

Theory Four: The Exodus took place in the middle of the Nineteenth Dynasty, with Ramesses II as either the Pharaoh of the oppression or of the Exodus.

The four theories as to the identity of the Exodus Pharaoh are shown in Figure 11 against the timeline of the Middle and Late Bronze Ages. Archaeologically speaking, these translate to a conquest (1) in the Middle Bronze IIB/C period, (2) at the end of Middle Bronze IIC and the beginning of Late Bronze I, (3) at the end of Late Bronze I, or (4) during Late Bronze IIB. In Part II and Part III, we will consider which of these periods contains archaeological evidence that provides the best match for the conquest as recorded in Joshua and Judges.

Early or Late?

Ussher’s identification of Ramesses as the Exodus Pharaoh and his date for this event are, to my knowledge, the first attempt to place the Exodus based on the two key verses that, today, drive the debate on the Exodus date:

8 Now there arose a new king over Egypt, who did not know Joseph. 9 And he said to his people, “Look, the people of the children of Israel are more and mightier than we; 10 come, let us deal shrewdly with them, lest they multiply, and it happen, in the event of war, that they also join our enemies and fight against us, and so go up out of the land.” 11 Therefore they set taskmasters over them to afflict them with their burdens. And they built for Pharaoh supply cities, Pithom and Raamses. (Exodus 1:8-11, NKJV)

Exodus 1:11 identifies the Israelites as the builders of the city of Ramesses. If the Israelites built that city, then logically it must have been during his reign. Therefore, some conclude that Ramesses II must be the Pharaoh of the oppression, the Exodus, or both. At the same time, we are given the date of the Exodus as relates to Solomon’s reign:

And it came to pass in the four hundred and eightieth year after the children of Israel had come out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over Israel, in the month of Ziv, which is the second month, that he began to build the house of the Lord. (I Kings 6:1, NKJV)

If the Exodus is dated to 480 years before Solomon, then we must look at that point in history for the events of the Exodus and the Pharaoh who would not let the people go. In his entry for the year 1012 BC, Ussher records:

“The foundation of the temple was laid in the four hundred eightieth year after Israel’s exodus from Egypt. This was in King Solomon’s fourth year of reign, on the second day of the second month (called Zif, Monday May 21).” (Annals of the World, Fifth Age, 466)

Thus, Ussher places the Exodus simultaneously in association with Ramesses II, in line with Exodus 1:11, and 480 years before Solomon, in line with I Kings 6:1. Given the poor understanding of Egyptian history in Ussher’s time, no conflict was perceived between these verses. Less than 200 years later, archaeology would change that.

When Champollion cracked the code of Egyptian hieroglyphs, it became possible to piece together a history of Egypt, not from later written histories such as the fragments of Manetho handed down through later authors, but from primary sources: the inscriptions found in the temples and tombs and from much older papyri. This did not happen all at once, and it was really only in the second half of the twentieth century that the timeline reached maturity. Yet, even today, Egyptologists continue to argue over the smaller details, and there remain multiple chronological options for certain periods, notably for us, the early Eighteenth Dynasty.

Solomon is now generally dated to 970-930 BC,[25] and 480 years before his year four would be 1446 BC. The reign of Ramesses II, however, is now generally dated to 1279-1213 BC, two hundred years later. Thus, based on our understanding of the history of Egypt and of the Kingdom of Israel, we cannot both advocate for Ramesses II as the Exodus Pharaoh and simultaneously place the Exodus 480 years before Solomon. Something has to give. Consequently, two competing theories developed: The late Exodus theory, placing the Exodus in the time of Ramesses II, and the early Exodus theory, which fixes the date of the Exodus in 1446 BC. The specific Pharaoh could then be Thutmose III or his son Amenhotep II, depending on which chronology you prefer. The earlier options, our Theory One and Theory Two, have largely been ignored by modern scholarship. The majority of secular archaeologists currently support the late Exodus theory, while some Christian archaeologists, such as Douglas Petrovich, and groups, such as Associates for Biblical Research (publishers of Bible and Spade), support the early Exodus theory.

Much of the early debate between these two theories was between biblical scholars and focused on the text. For those who prefer the late Exodus date, I Kings 6:1 is a problem. The solution is an alternative interpretation of this verse. The period of 480 years is interpreted to represent twelve ideal generations of forty years each. However, in the time of the Egyptian New Kingdom, the actual average time from father to son was closer to twenty-five years.[26] Twelve times twenty-five is 300 years, and three hundred years before year four of Solomon would be 1266 BC, or right in the middle of the reign of Ramesses II. Thus, by interpreting the 480 years to refer to twelve generations and shortening the length of those generations, late Exodus proponents can resolve the conflict.

For those who support the early Exodus theory, the problem is the identification of the city of Raamses as one of the cities constructed by the Israelites. The solution in this case does not require any alternative mathematics. The city of Pi-Ramesses was located adjacent to and on top of the more ancient city of Avaris, which Josephus identified as the city where the Exodus began. When Joseph settles his family in Egypt, he does so in the “land of Rameses” (Genesis 47:11), but this was at least two hundred years before the Exodus, and long before Ramesses II was even born. The assumption then is that the name “Ramesses” is an update made by a later editor to replace the name of Avaris, so that his readers would know the location, in the same way that we would use New York to refer to the former Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. If this is true, there need not be any connection between the events in the Exodus and Ramesses II. Exodus 1:11 should then be read something like “And they built for Pharaoh supply cities, Pithom and Avaris, which is now called Raamses”. With this assumption, the Exodus can then safely be placed in 1446 BC. The two positions are summarized in Table 2

Early or Late? |

||

| Verse | Early Exodus | Late Exodus |

| Exodus 1:11 : Pithom and Raamses | The name Raamses is a later edit that replaced the original name of Avaris. | The name Raamses indicates that these cities were constructed during the reign of Ramesses II |

| I Kings 6:1 : 480 years before Solomon | 480 literal years | Twelve ideal generations of forty years each, which equates to 300 actual years using a twenty-five-year generation |

| Table 2 | ||

These arguments in favor of an early or late Exodus are based on the biblical text alone, not on archaeology or any extra-biblical sources. Both have strong adherents, but neither side can win the argument with textual criticism or logic alone. We need facts and evidence to determine which one, if either, is correct. It’s sort of like two rival football fans making the case for the superiority of their teams before the season has started. The only way to settle the argument is ‘on the field’, or in this case, in the field.

John Bimson[27] traces the first opinion on this subject from an archaeologist, as opposed to a theologian, to C.R. Lepsius, a German Egyptologist who, in 1849, identified Ramesses II as the Exodus Pharaoh. Lepsius’ view was supported by Flinders Petrie following the discovery of the Merneptah stele in 1896. As the timeline of Egyptian history was refined, a second school emerged that favored Thutmose III as the Pharaoh of the oppression and his son Amenhotep II as the Pharaoh of the Exodus. A significant proponent of the earlier date was John Garstang, excavator of Jericho in the 1930’s. His 1931 book Joshua-Judges seeks to demonstrate the evidence for the early Exodus in several passages based on then-current knowledge and his interpretation of his findings at Jericho. On the other side of the debate in the 1930’s and later was none other than William Albright, who espoused the Ramesses II theory. When later excavations by Kathleen Kenyon in the 1950’s demonstrated that Garstang had misdated the fall of Jericho, much of the support for the early Exodus evaporated. In the archaeological community, the Ramesses II theory has since become gospel, with the earlier Exodus theory supported primarily by Christian groups and individuals.

I find this current state of affairs most interesting. On the one hand, the archaeological community insists that the Exodus, if there was one, must have taken place in the time of Ramesses II, while at the same time insisting that there is no evidence for it in that time period. Of course, if there was strong evidence for an Exodus at the time of Ramesses II, there would be no need for me to write this article! Having reviewed the various theories on the identity of the Exodus Pharaoh, perhaps it is time to begin to look at the archaeological evidence, and we will do that in Part II.

The Exodus Pharaoh: Part II – The Egyptian Evidence ->

Footnotes

[1] See I Kings 14:25, II Kings 17:4, II Kings 19:9, II Kings 23:29. Of these, only the last two, Taharqa and Necho, are conclusively identified and securely dated

[2] Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Vol 3 §617, p263-4 modernized by author

[3] See www.thebiblicaltimeline.org/Joseph

[4] Hudec, et. al. (2023), pp23-24

[5] See MacDonald (1980) and Redmount (1995) for the archaeology of Tell el-Maskuta

[6] The battle of Marathon was in 490 BC, and the battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC

[7] Rohl (2015), p 132. In Egyptian, “hotep” means “to be satisfied” or “to be at peace”. Sobek is the crocodile god, and so the name means “the crocodile god is satisfied”.

[8] Sobekhotep IV was one of the longer reigning Pharaohs of the Thirteenth Dynasty, with a reign of perhaps ten years. He succeeded his brothers Neferhotep I and Sihathor. Clearly, the oppression was already underway at the time of Moses’ birth, but we don’t know how long it had been going on

[9] See Rohl (1995), Rohl (2015), James (1993). Rohl associates Timaus with Dudimose, with the Hyksos invasion being a consequence of the destruction from the plagues and the loss of the army in the Red Sea.

[10] Against Apion, 1:14

[11] Pritchard (1969), Ancient Near Eastern Texts, p233

[12] See Against Apion, Book I, 24-31

[13] Africanus, as preserved in George Syncellus Chronographia, calculates as follows: 40 years from Moses to Joshua (Exodus to death of Moses), 25 years for Joshua, 30 years for the elders that outlived Joshua, 490 years for the Judges, 90 years for Eli and Samuel. If we include Saul with Samuel, as Josephus does, we then need to add 44 years for David and the first four years of Solomon for a total of 719 years.

[14] This is the same Apion who was the target of Josephus’ work Against Apion. Unfortunately, none of Apion’s works survive.

[15] See Syncellus (1829), p 120 for the original Greek and Latin. Eusebius preserves a similar quote in Preparation for the Gospel, Book 10:10.16

[16] Syncellus (1829), p 124. Translated from the Latin. This is but part of an extended passage where Syncellus attacks Eusebius on this point.

[17] Ibid, p 127, from the Latin via Google Translate with my amendments

[18] Ibid, p 125

[19] While Syncellus is 1200 years less “ancient” than Herodotus, he still had access to many of the old sources that were subsequently lost in the Middle Ages.

[20] Ibid, p 127, from the Latin via Google Translate with my edits

[21] Ibid, p 128, from the Latin via Google Translate with my edits and redactions

[22] Ussher (1650), 3:159, 170-171. Following Manetho’s identification of Amenophis as the son of Ramesses II. Ussher places Joseph in the preceding Eighteenth Dynasty under an earlier Amenhotep.

[23] JP dates refer to the Julian Period which Ussher begins on January 1, 4713 BC.

[24] Ramesses II did have a son by the name of Amenhotep, but he did not outlive his father and never became Pharaoh.

[25] These dates derive from Thiele (1983). While there are alternative solutions, Thiele remains the definitive work on the subject. Ussher dates Solomon forty-six years earlier. Ussher dates the fall of Jerusalem two years earlier than Thiele, in 588 BC. The remaining forty-four year difference is due to errors in Ussher’s timeline for the kings of Israel and Judah.

[26] As calculated from kings lists and other available records. Of course, the first son did not necessarily succeed his father, and there are other factors that might cause the years between generations for royalty to be higher than for the general population.

[27] For a detailed summary of the history of the shifting opinions in the Ramesses II vs. Thutmose III / Amenhotep debate, see Bimson (1981), and in particular Section 0.3 of the Introduction. Bimson provides a shorter summary in Bimson (2025). Both are available online.

References

The following is a list of the works referenced above

Bimson, J. J. (1981). Redating the Exodus and Conquest. Sheffield: The Almond Press.

Bimson, J. J. (2025). An Alternative Paradigm for Israel’s Origins in Canaan. In P. G. van der Veen, R. Wallenfels, & P. James (Eds.), Assyria and the West (pp. 167-204). Bicester, United Kingdom: Archaeopress.

Breasted, J. H. (1906). Ancient Records of Egypt. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Clement of Alexandria. (2016). Clement of Alexandria (Kindle ed.). (P. Schaff, Ed.) Aeterna Press.

Eusebius. (325 / 2015). Chronicle. Beloved Publishing.

Eusebius. (2025). Praeperatio Evangelica (Preparation for the Gospel) (Kindle Edition ed.). (O. A. gpt-4o-mini, Trans.) Appian Way Press.

Garstang, J. (1978). Joshua Judges: Foundations of Bible History. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Kregel Publications. Reprint of the original 1931 book.

Hudec, J. et. al. (2023). Between Tombs and Defence Walls: Tell el-Retaba in Seasons 2019 and 2020. Agypten und Levante, 21-74. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/27331096

James, P. (1993). Centuries of Darkness (US ed.). London: J. Cape.

Josephus, F. (1999). The Complete Works of Josephus. (P. L. Maier, Ed., & W. Whiston, Trans.) Grand Rapids, Michigan: Kregel Publications.

MacDonald, B. (1980). Excavations at Tell el-Maskhuta. The Biblical Archaeologist, 49-58. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3209753

Pritchard, J. B. (1969). Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Redmount, C. A. (1995). Ethnicity, Pottery, and the Hyksos at Tell El-Maskhuta in the Egyptian Delta. The Biblical Archaeologist, 182-190. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3210494

Rohl, D. M. (1995). A Test of Time: The Bible – From Myth to History. London: Century.

Rohl, D. M. (2015). Exodus: Myth or History? St. Louis Park, Minnesota: Thinking Man Media.

Syncellus, G. (1829). Chronographia (Vol. 1). (W. Dindorf, Ed.) Bonnae : E. Weber.

Thiele, E. R. (1983). The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan.

Ussher, J. (1650 / 2003). The Annals of the World. (L. Pierce, & M. Pierce, Eds.) Green Forest, Arkansas: Master Books.