The Exodus Pharaoh Part III – The Conquest

Photo: Portion of the Survey of Western Palestine, Sheet XVII, showing el-Bireh and el-Jib

<- Part II: The Egyptian Evidence

The Exodus Pharaoh – Part III: The Conquest

In Part I, we identified four candidates, or theories, for the Pharaoh of the Exodus. In Part II, we considered the historical background of each theory and the evidence found in Egypt relevant to each. Now in Part III, we will look at the evidence in Canaan to support the conquest that followed.

The Limits of Archaeology

Before we begin to look at the specifics of what has been found by archaeology, we need to first consider what we are looking for and the limits of our approach. Unfortunately, unlike the Egyptians, the Israelites and the Canaanites that preceded them did not leave monumental inscriptions in stone. There are only three monumental inscriptions known in what is today Israel and Transjordan (The Tel Dan Stele, the Meshe stele, and the Hezekiah tunnel inscription), all dating from at least six hundred years after the Exodus. Most likely, the inhabitants of Canaan and Israel wrote on perishable media such as parchment, and these did not survive.[1] What should we expect to find then? What would we consider to be evidence of a conquest by the Israelites? How can we be sure?

What Can We Find?

Archaeology is ultimately the study of material remains, of what is left behind by people and events. In this case, there are two things that we might consider: a change in the material culture, and evidence of the city destructions described in Joshua and in Judges 1. When archaeologists speak of material culture, they mean the pottery styles, the religious artifacts, and the architecture. Generally speaking, if an area were invaded by an alien group, we would expect to see a change in the material culture to reflect the culture of the newcomers. This was certainly the case with the arrival of the Philistines, who brought new pottery styles (what is known as “Philistine Ware”), new gods, and other influences. However, when we consider the arrival of the Israelites in Canaan, we need to be careful in assuming an associated change in the material culture. If we take the biblical account at face value, the Israelites lived in Canaan for over two hundred years, from the arrival of Abraham until Jacob’s descent into Egypt, and during that time they were “nomadic pastoralists”,[2] what today we might call Bedouin. As such, their material culture would have reflected that of their Canaanite neighbors. The next stop was Egypt. Manfred Bietak, the excavator of Avaris, described the pottery of those who departed at the time of our Theory One as “Egyptianized Canaanite”,[3] or Canaanite with Egyptian influences. Those who occupied Avaris prior to our Theory Two had a similar material culture. A later Exodus in line with Theory Three or Theory Four would have likely included many Canaanite slaves who might retain their original culture, depending on how long they had been in Egypt. In addition, we should consider that, according to Judges, the Israelites assimilated into Canaanite culture:

5Thus the children of Israel dwelt among the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites. 6And they took their daughters to be their wives, and gave their daughters to their sons; and they served their gods. (Judges 3:5-6, NKJV)

When you put all of this together, it suggests that the culture of the Israelites on their arrival was very much Canaanite, and any Egyptian influences either disappeared during their time in the wilderness or shortly after. Arguably, any pottery with Egyptian influences would not be seen as evidence of the Israelites by the archaeologist, given the proximity to and ongoing trade with Egypt. Thus, again taking the biblical text at face value, we should not be looking for any significant cultural break with the arrival of the Israelites. In fact, their arrival is likely to be completely undetectable in the material culture.

If we cannot expect to see evidence of the conquest in the material culture, we can expect to find evidence of the city destructions as described in the book of Joshua and in Judges 1. There are forty-nine cities mentioned in those passages as having interacted with the Israelites in some fashion: destroyed, defeated in battle, placed under tribute, etc. Not all of these sites have been reasonably identified, and of those that have, not all have been excavated. For the purpose of this article, I will focus on four sites: Jericho, Ai, Gibeon, and Hazor, and provide a general summary of the others at the end. However, before we begin, we need to consider the potential pitfalls of this approach

Identification of Sites

The first challenge we must face is to correctly identify the sites that we are excavating. For example, let’s say we excavate an ancient city mound or tell, thinking it is Ai, but in fact it is a different city. The conclusions drawn from such an excavation with respect to the truth or fiction of the biblical account of the battle of Ai and the timing of those events would be incorrect. Clearly, it is critical to get the identifications correct before we even consider the archaeological finds. But how do we know that we are excavating in the right place?

In some cases, a city has been occupied pretty much continuously down through the ages and has retained some form of its name. Jerusalem is an obvious example of this, and no one would suggest that the Jerusalem of today does not correspond to that of the time of Joshua. In cases when a city mound has long been abandoned, it may still retain some form of its ancient name (though in Arabic, not Hebrew) as a clue to its identity. We may also have ancient sources that describe the location of a city with respect to that of other, known locations. The Onomasticon of Eusebius is just such a source and is useful in locating biblical places. Sometimes the archaeologist will get lucky and find some sort of inscription that confirms the identity, such as a boundary marker (Gezer), jar handles (Gibeon), or a cuneiform tablet (Hazor). However, in many cases, site identification remains a sort of very educated guesswork, and this creates the possibility that it is incorrect. The potential that a site identification is incorrect is generally reflected by the presence of alternative opinions and identifications, and we will look at those where applicable.

Incomplete Excavations

When a site is excavated, it is rarely, if ever, excavated completely. Limits on time and funding will usually limit the excavations to specific areas identified as being of interest to the archaeologist. It’s true that some sites have been excavated quite extensively, but even so, it is always possible that key finds have been missed, or rather, not found yet. Conducting an archaeological dig is a bit like taking a statistical sample, and as such, it is subject to the same risks when drawing conclusions. Specifically, it is possible to get both false positives and false negatives with respect to whatever theory is being investigated. If you fill a bag with ninety-five blue marbles and five red marbles, and then reach in and pick out three marbles (without looking), it is certainly possible, if not likely, that all three will be blue. But it would be wrong to conclude that, therefore, all of the marbles in the bag must be blue. Fortunately for those of us who are not trained archaeologists, once results are published, there are often alternative hypotheses and theories offered by others in the field that we might consider if one of these errors is suspected. We may also find that conclusions change as additional excavations are conducted (or as more marbles are pulled from the bag, so to speak).

Asking the Wrong Questions

Perhaps the most dangerous sort of error in any scientific (or in this case, pseudo-scientific) discipline is asking the wrong questions or, put another way, starting with the wrong assumptions. For example, an archaeologist might start with the hypothesis that a significant change in material culture is required as evidence of the conquest. However, as noted above, this hypothesis is based on the assumption that the material culture of the Israelites was different from that of the people that they conquered. If, as I have proposed above, the material culture of the Israelite invaders was substantially similar to that of the Canaanites that they replaced, then this hypothesis is incorrect, as are any conclusions drawn from it (for example, claiming that there was no conquest because there is no evidence of a change in material culture). Thus, it is critically important to understand the assumptions and biases that lie behind the archaeological findings.

Archaeology is not just about what was found, but about how to interpret those findings. Perhaps a piece of pottery was found at a specific location. That is a fact. However, what period to assign that pottery to (e.g., Middle Bronze IIC vs. Late Bronze I) is a matter of interpretation. Different archaeologists may reach different conclusions, and here again, there are biases and assumptions in play. This may, in turn, lead two archaeologists to come to different interpretations of the same hard evidence. With these thoughts in mind, we will now consider the evidence for the conquest.

Evidence For the Conquest

There are a total of forty-nine cities that the Israelites interact with in the book of Joshua and in Judges 1. Of these, thirty-four have been reasonably identified, and thirty have been excavated to the point where we can draw conclusions (assuming we are comfortable with the identifications). The arguments around when, or if, the conquest happened usually center on three of these, given their prominence in the narrative, and the testimony that they were burned by Joshua: Jericho, Ai, and Hazor. To this, I will add one more city that occupies a significant place in the text, Gibeon.

Jericho

Upon crossing the Jordan River, the city of Jericho stood as an obstacle between the Israelites and a move further west into the highlands. Jericho, while not a large city compared to other cities of Canaan, was the only significant walled city in the southern Jordan valley west of the river. By conquering Jericho, the Israelites would establish a safe beachhead from which to conquer the rest of Canaan, and so it was only natural that this was Joshua’s first objective.

The location of Jericho has never been in doubt for the simple reason that there are no other candidates. Ancient Jericho can be found at Tell es-Sultan, adjacent to the modern city. Jericho has received a lot of attention from archaeologists, both because of its prominence in the book of Joshua and because the biblical text contains a lot of archaeologically verifiable information, specifically:

-

- Jericho was a walled city, with houses built into the wall (Joshua 2:15, 6:1)

- The attack on Jericho occurred in the spring, shortly after Passover (Joshua 5:10)

- The walls of the city collapsed in such a way as to allow the Israelites easy entry (Joshua 6:20)

- The city was subsequently burned (Joshua 6:24)

- The city was not rebuilt as a walled city until the time of Ahab, King of Israel (Joshua 6:26, I Kings 16:34)

- However, the site was occupied during at least two periods in the intervening years (Judges 3:13, II Samuel 10:5)

Jericho, it seems, is the perfect place to establish when the conquest occurred because, according to the book of Joshua, it was not rebuilt until much later. If we can establish when the last pre-Israelite (i.e., pre-Iron Age II) city was destroyed, then we will have our conquest date (at least approximately).

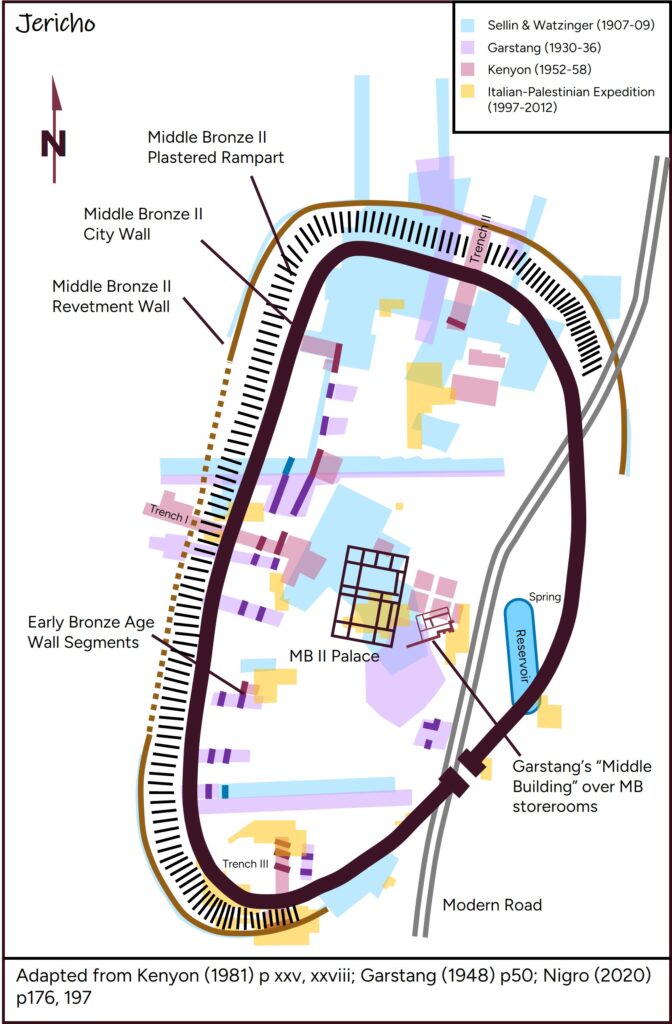

Figure 1: Excavations at Jericho

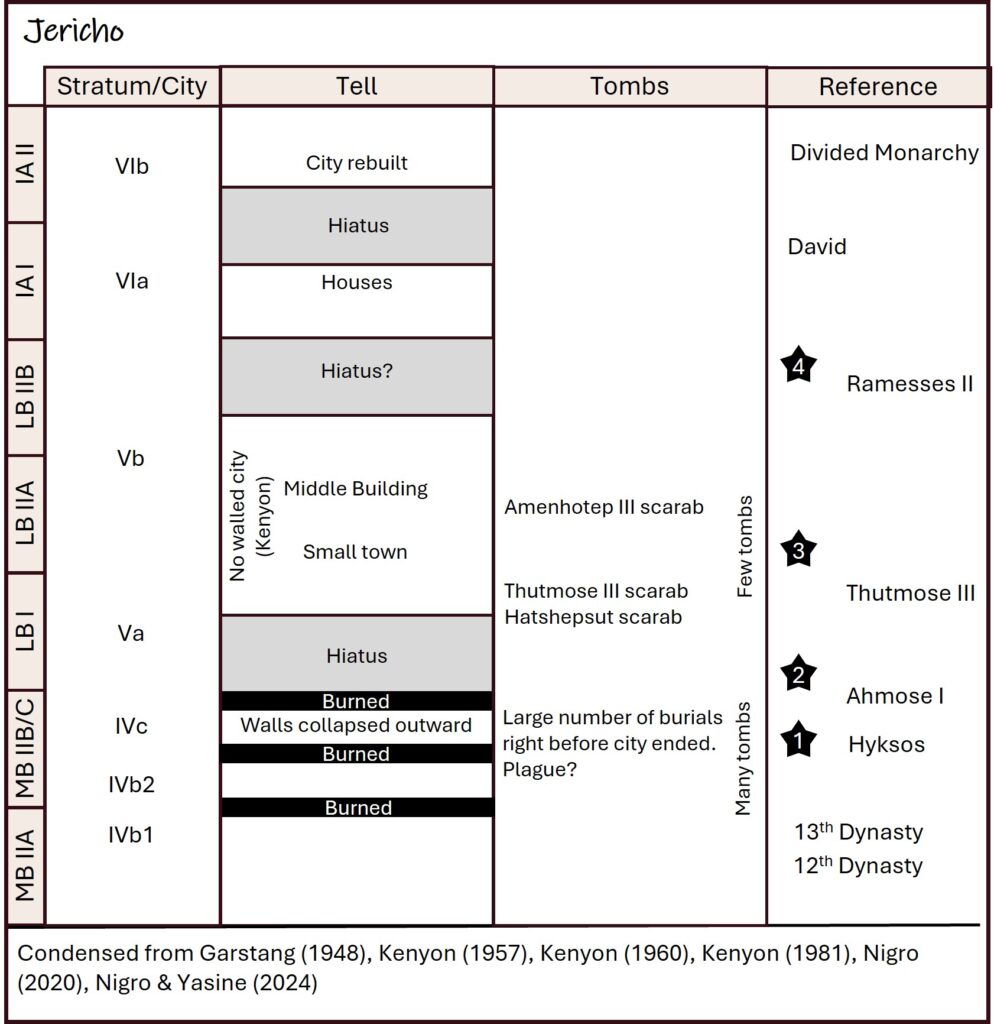

Jericho has been excavated extensively, first by the German team of Sellin and Watzinger from 1907-1909, followed by John Garstang from 1930-1936, Kathleen Kenyon from 1952-1958, and by a joint Italian-Palestinian team from 1997 to at least 2023 (see Figure 1). Garstang claimed to have identified a city that was destroyed at the end of Late Bronze I, consistent with our Theory Three. However, Garstang made several errors in his dating that were later corrected by Kenyon. With the completion of Kenyon’s work, and considering also the work of her predecessors, the picture of Jericho was as follows (see Figure 2):

-

- The walled city of Jericho was destroyed at the end of the Middle Bronze IIB/C. This city, known as City IVc, fits the criteria in Joshua.

- Houses were built into the city wall in at least one area.

- The walls had collapsed outward, with the debris ending up at the bottom of the rampart, providing a ready-made path into the city.

- The remains of the city had then been burned in a great fire.

- Many jars of burned grain were found, suggesting that the city had not suffered a long siege and that it was destroyed in the spring, shortly after the grain harvest. This also indicates that the food resources of the city were not taken before it was burned.

- While there was evidence of Late Bronze Age burials in Jericho’s tombs and some level of occupation on the tell, there was no walled city at Jericho during all of the Late Bronze Age. The volume of Late Bronze burials is tiny compared to that of the preceding Middle Bronze Age, suggestion a much smaller population or reuse of the tombs by the local nomadic population.

- Garstang had identified a structure on the tell known as the “Middle Building,” which was occupied in the Late Bronze Age IIA period.

- The walled city of Jericho was destroyed at the end of the Middle Bronze IIB/C. This city, known as City IVc, fits the criteria in Joshua.

Figure 2: Stratification of Jericho

While City IVc is an excellent fit for the description of Jericho in the book of Joshua, it is simply way too early for the majority of the archaeological community, who would align the conquest with Theory Four and place it in the Late Bronze Age IIB. The absence of evidence of a Late Bronze Age city would lead William Dever to remark that, “Joshua destroyed a city that wasn’t even there.”[4] Dever was not alone in this sentiment, and the result of Kenyon’s work was ultimately an abandonment of the conquest as a historical reality by most archaeologists.[5] Secular archaeologists responded by developing alternative theories of the origins of Israel that ignored the biblical text, which they generally believed to have been written down only during the time of Josiah or later, too distant from the events described to be reliable. The Christian community, on the other hand, has generally responded in one of three ways to “solve” the problem of Jericho.

-

- Look for evidence of a Late Bronze city

- Attempt to redate City IV to the Late Bronze I to align with Theory Three

- Revise the chronology to align the fall of Jericho City IV at the end of the Middle Bronze Age with the conquest date of 1400 BC (Theory One or Two)

Kathleen Kenyon was the first to suggest that perhaps a Late Bronze city had existed, but its remains had been eroded away or removed by later construction. Kenyon concluded in her book Digging Up Jericho:

“As concerns the date of the destruction of Jericho by the Israelites, all that can be said is that the latest Bronze Age occupation should, in my view, be dated to the third quarter of the fourteenth century B.C. [1350-1325]. This is a date which suits neither the school of scholars which would date the entry of the Israelites into Palestine to c. 1400 B.C. [Theory Three] nor the school which prefers a date of c. 1260 B.C. [Theory Four] It must be admitted that it is not impossible that a yet later Late Bronze Age town may have been even more completely washed away than that which so meagerly survives. All that can be said is that there is no evidence at all of it in stray finds or in tombs.”[6]

The recent excavations by the joint Italian-Palestinian expedition led by Lorenzo Nigro have renewed interest in the possibility that there was, in fact, a city at Jericho c. 1400 B.C. Nigro claims to have found evidence of city walls from the Late Bronze I period (Theory Three) built on top of the destroyed Middle Bronze remains of City IVc. However, his results are not universally accepted. Clearly, there was some occupation of Jericho in this period, as evidenced in both the tombs and the Middle Building. The question is, was the city walled at that time? However, Nigro has not, to my knowledge, found any evidence of a city in the Late Bronze IIB as required by Theory Four, consistent with Kenyon’s statement above.

The second approach was championed by Bryant Wood and his colleagues at the Associates for Biblical Research, at least until recently. Wood argued that the pottery of City IVc should be dated to the Late Bronze I, in spite of the absence of the imported Cypriot pottery styles that are characteristic of this period.[7] Wood argued that Jericho’s distance from the coast and the fact that many of the areas excavated were the houses of the poorer people would preclude the presence of expensive imports, and the dating should be assigned based on the styles of more basic domestic pottery, which he felt belonged to the Late Bronze I. We will discuss Wood’s arguments in more detail below in the section on Ai.

The final option is to adjust the dating of the end of the Middle Bronze Age, aligning the fall of City IVc with a date of c. 1400 BC. This effectively aligns Theory One or Two with the date given in I Kings 6:1. In his PhD thesis and subsequent book, John Bimson proposed that the Middle Bronze Age extended as late as 1400 BC (vs. the generally accepted end date of 1550 BC), to align not just Jericho, but other Middle Bronze Age settlements with the conquest.[8] This approach did not receive much attention because it did not align with the pottery evidence. An alternative approach was suggested by chronological revisionists such as David Rohl and Peter James, who were later joined by Bimson.[9] They note that the current dates for the Pharaohs of the Egyptian New Kingdom, and thus the archaeological periods to which they belong, hang by a single thread: the association of “Shishak” of I Kings 14:25 with Pharaoh Sheshonq I, founder of the Twenty-Second Dynasty. Breaking this link allows for a compression of the Egyptian Third Intermediate Period based on evidence that the dynasties of this period overlapped more than the current timeline allows. The net result is to shift the Egyptian timeline relative to the biblical timeline (see New Chronology timeline). This approach, while not widely accepted, maintains the alignment between the historical events and the pottery sequence.

While Jericho would ideally provide us a clear answer as to the dating of Joshua’s conquest, we instead find a cloud of conflicting opinions. To resolve these, we will need to cast a wider net, so to speak. Joshua 12 lists thirty-one kings that Joshua defeated in battle. While only three of these (Jericho, Ai, and Hazor) are identified as being burned, the others, at a minimum, must have existed at the time of the conquest. Perhaps we can get a clearer answer by considering all of the relevant sites collectively.

A Tale of Two Cities: Bethel and Ai

Following their victory at Jericho, the next step for Joshua and the Israelites is to gain a foothold in the central hill country. Proceeding west from Jericho up the ancient paths into the hills would have brought them to the vicinity of Ai. The city of Ai first appears in Genesis in relation to Abraham’s second stop in Canaan:

And he moved from there to the mountain east of Bethel, and he pitched his tent with Bethel on the west and Ai on the east; there he built an altar to the Lord and called on the name of the Lord. (Genesis 12:8, NKJV)

This provides two important pieces of geographical information. First, Ai is east of Bethel, and second, there is a mountain east of Bethel suitable for Abraham’s campsite. The relationship between Bethel and Ai is also mentioned in Joshua:

Now Joshua sent men from Jericho to Ai, which is beside Beth Aven, on the east side of Bethel, and spoke to them, saying, “Go up and spy out the country.” So the men went up and spied out Ai. (Joshua 7:2, NKJV)

Again, Ai is east of Bethel, and this verse adds an additional piece of information, that it is close to Beth Aven. In the Bible, as in other ancient texts, only the four cardinal directions are used: north, south, east, and west. Thus, “east” could mean anything in the ninety-degree arc between northeast and southeast, and perhaps we should allow for some degree of imprecision. Bethel is consistently the reference point given in locating Ai, and so if we are to identify an archaeological site that corresponds to Ai, we must first locate Bethel.

Edward Robinson, in 1841, was the first to propose that the village of Beitin (Baytin on modern maps) was the site of ancient Bethel. “Beit” is the Arabic equivalent of the Hebrew “Beth” as seen in place names such as Beit She’an (Beth Shean). The transformation of “el” into “in” when going from Hebrew to Arabic is not uncommon, and so this was a logical choice, and it was generally accepted. With Bethel identified, the search could now begin for Ai, and several proposals were floated by different scholars. The debate continued until 1924, when William Albright, in Appendix V of his report on Gibeah of Saul, proposed that Ai was located at et-Tell.[10] It seems that this view was immediately and enthusiastically accepted by the archaeological community and has largely remained so ever since. Even though the specifics of et-Tell didn’t match the biblical description. Here is as clear a case as I have seen of opinion becoming fact, almost solely due to the reputation of the one giving the opinion, in this case, Albright.

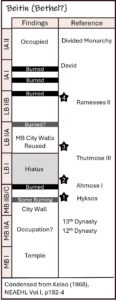

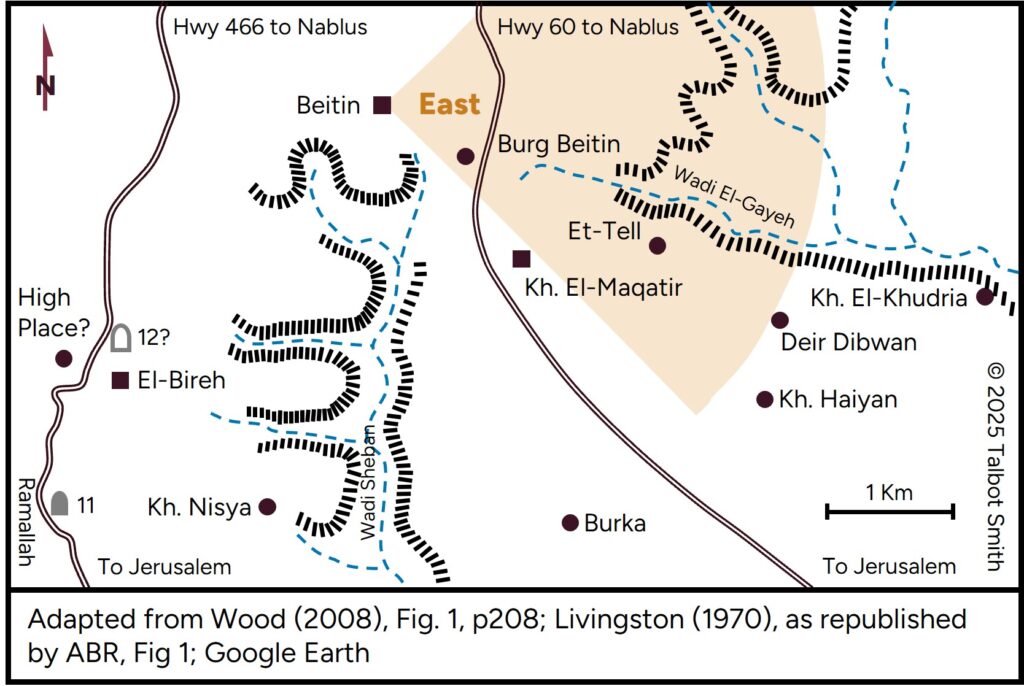

Figure 3: Archaeology of Beitin

Beitin was subsequently excavated, initially by Albright in 1934, and then by James Kelso for three seasons between 1954 and 1960. Albright and Kelso published a combined report of their work in 1968.[11] The excavations uncovered a city that was occupied beginning in Middle Bronze I and fortified in Middle Bronze IIB/C (See Figure 3). Following a destruction at the end of MB IIB/C, it was apparently abandoned for all of Late Bronze I, before being reoccupied in Late Bronze IIA. Interestingly, the Middle Bronze fortification system was repaired, not replaced, and used for eight hundred years until the city was destroyed by the Persians. One of the primary objectives of these excavations was to find the temple of the golden calf set up at Bethel by Jeroboam (I Kings 12:28-29). This may have been a case of asking the wrong question, as the biblical text references high places and not a temple, and more recent discoveries at Dan, the site of the other golden calf, indicate only a high place in this period. Nonetheless, no temple or high place of the period of the Kingdom of Israel (Iron II) was discovered, and thus, there was no confirmation that the site is indeed Bethel.

The situation at et-Tell, now presumed to be Ai, was quite different. Et-Tell was initially excavated by Judith Marquet-Krause in 1933-35, but she unfortunately passed away before she could continue her work. Joseph Callaway then excavated for an additional seven seasons between 1964 and 1972, and it is to him that we owe the major report on the site.[12] While Albright claimed to have found Middle Bronze Age pottery sherds on the mound,[13] Callaway found only the remains of a significant Early Bronze Age city and a small Iron Age village – and nothing in between. In other words, no evidence of occupation corresponding to any of our four Theories! Callaway recognized this issue and opened his 1968 article on the excavations at et-Tell with this statement:

“’At Ai [et-Tell], as at Jericho,’ Father John L. McKenzie observed, ‘archaeology has raised more problems than it has solved.’ I can find no one who has studied the conquest of Ai since the Marquet-Krause excavations in 1933-35 who would disagree. Ai is simply an embarrassment to every view of the conquest that takes the biblical and archeological evidence seriously.”[14]

In other words, if et-Tell was indeed Ai, the archaeological evidence stood in sharp contrast to what was recorded in the book of Joshua, as there was no city there for Joshua to destroy. To his credit, Callaway considered the possibility that Ai was in fact located elsewhere and excavated several other sites nearby, notably Khirbet Haiyan and Khirbet el-Khudria. However, he did not find any signs of Middle or Late Bronze occupation, other than a single Middle Bronze II tomb. Like Albright before him, Callaway concluded that there was no other candidate for Ai in the areas east of Bethel. Fortunately, our story does not end there.

As early as 1970, David Livingston proposed that Bethel was not located at Beiten, but further south at el-Bira.[15] Critical to this identification was the location of Bethel given by Eusebius:

“Baithel. Now it is a village 12 milestones away from Ailia [Jerusalem] on the way to Neapolis [Shechem, modern Nablus], on the right.” Onomasticon, 41

Figure 4: Candidates for Bethel and Ai

Livingston consulted the Survey of Western Palestine of 1883 and found that, at that time, the third and fifth Roman milestone north of Jerusalem were still extant. Another milestone had been found about a mile south of el-Bira which Livingston proposed to be the eleventh and by extrapolation, the twelfth milestone would be located in el-Bira, Beiten being approximately two miles further north.[16] I have indicated the location of these milestones on the left side of Figure 4. Livingston would later propose that Ras et-Tahuneh, a hill on the west, or left side of the Roman road at el-Bira, was the likely site of the high place of Bethel, as it had the remains of an elevated platform and was found by archeological surveys to have significant quantities of Iron II pottery sherds.[17] Based on this new identification of the location of Bethel, Livingston proposed Khirbet Nisya as the site of Ai and would spend much of his career excavating there. Unfortunately, his work did not uncover a Middle or Late Bronze city at that location, only perhaps a small farmstead.[18] And so the search continued.

Ultimately, archaeologist Bryant Wood identified Khirbet el-Maqatir as the site of Joshua’s Ai, and he would excavate there from 1995 to 2014.[19] This site is quite close to et-Tell, but just far enough south or west to not be “east” of Beiten. It is, however, certainly east of el-Bira (see Figure 4). Wood provides a number of characteristics that the site of Ai must meet, according to Joshua. I don’t agree that all of his requirements are clear from the text, but that doesn’t mean I don’t agree with his identification. I have summarized seven of the critical characteristics and how they fit each site in the table below.

| Characteristic | Et-Tell | Kirbet el-Maqatir |

|---|---|---|

| Beside Beth Aven (Joshua 7:2) | No candidate for Beth Aven identified | Yes, with Beiten as Beth Aven |

| East of Bethel (Joshua 7:2) | Yes. East of either option for Bethel | Yes. East of el-Bira, marginally east of Beiten |

| A small city (Joshua 7:3) | No | Yes |

| Smaller than Gibeon (Joshua 10:2) | No | Yes |

| Ambush location to the west of Ai (Joshua 8:12) | No | Yes. In the valley of the Wadi Sheban |

| Gate on the north side of the city (Joshua 8:13) | No | Yes |

| Burned (Joshua 8:28) | Not occupied | Burned, MB IIC or LB I |

Table 1: Characteristics and Identification of Ai.

At last, it seems we have a viable candidate for Ai, and we can turn our attention to what was found there, and to the implications for the Exodus date.

The Pottery Debate

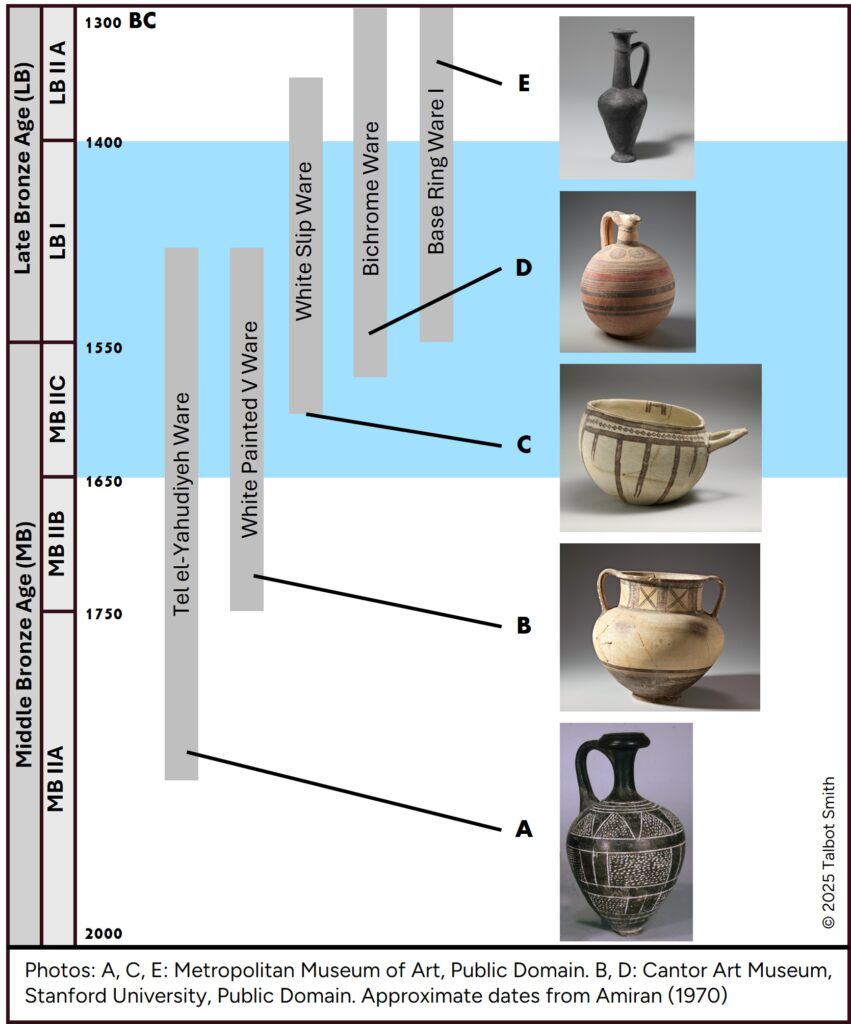

Wood’s excavations determined that Khirbet el-Maqatir was a small city constructed in the Middle Bronze IIB/C period, and it was subsequently destroyed by fire. Wood dates this destruction to the Late Bronze I, consistent with an Exodus in the time of Amenhotep II (Theory Three), an identification which Wood has consistently advocated elsewhere. Khirbet el-Maqatir had been surveyed in 1981 by Israel Finkelstein and his team. However, that survey found only Middle Bronze and Iron Age I pottery, nothing from the Late Bronze Age.[20] David Rohl has disputed the identification of the pottery and an accompanying scarab as Late Bronze Age, instead identifying both as belonging entirely to the Middle Bronze Age.[21] I had the opportunity to ask David about the Khirbet el-Maqatir pottery and why he felt it was MB IIB/C and not LB I. His response was that the Khirbet el-Maqatir pottery was “the same as Jericho City IV.”[22] As we will see shortly, the pottery found beneath the MB IIB/C destruction layer at Gibeon also matched that of Jericho City IV, indicating that all three sites were destroyed at approximately the same time. But when was that?

Figure 5: Middle and Late Bronze Age Pottery Styles

To understand this argument, it is necessary to understand a bit about pottery dating. Pottery styles change gradually over time, just as fashions do today, although much more slowly. Particular styles of pottery come and go, changing gradually over the lifetime of their production. Many styles bridge multiple archaeological periods, and in order to date a destruction layer, it is necessary to consider the entire collection, or assemblage, of pottery found. Figure 5 shows some of the significant types of pottery of the Middle and Late Bronze Ages. A date for the destruction of Khirbet el-Maqatir at the end of the Late Bronze I period (corresponding to Wood’s placement of the conquest in circa 1400 BC) would require the presence of Late Bronze forms such as White Slip Ware, and imported Cypriot Bichrome Ware and Base Ring Ware. However, Wood does not report findings of any of these pottery styles. It would also require the absence of older styles that faded out in the early LB I, such as Tell el-Yahudiyeh Ware and White Painted V Ware. As noted above, Wood has argued that the absence of Cypriot Bichrome ware in the City IV destruction layer at Jericho should not be used to argue that this site was destroyed in the Middle Bronze Age (i.e., before the advent of this pottery).[23] Bichrome Ware was imported from Cyprus, and would have appeared first on the coast and gradually worked its way inland. But this process would have likely been complete within a decade, whereas Wood’s argument requires that approximately one hundred and fifty years after this pottery first reached the shores of Canaan, it had still not made its way to Jericho. This argument is even weaker with respect to Ai, with its location in the central highlands, and weaker still with respect to Gibeon, on the road from the coast to the highlands, and which was “like one of the royal cities” (Joshua 10:2), and clearly affluent. Yet the same pottery was found in all three, and all three show an absence of bichrome ware in their destruction layers.

Gibeon

After Jericho and Ai, the only other city to warrant an extended narrative in the book of Joshua is Gibeon; thus, it’s appropriate that we make this our next stop. Following the victory at Ai, the people of Gibeon deceived Joshua and the Israelites, securing a peace treaty. However, when their ruse was discovered, Joshua condemned them to be slaves to the Israelites.

22 Then Joshua called for them, and he spoke to them, saying, “Why have you deceived us, saying, ‘We are very far from you,’ when you dwell near us? 23 Now therefore, you are cursed, and none of you shall be freed from being slaves—woodcutters and water carriers for the house of my God.” (Joshua 9:22-23, NKJV)

Threatened by this alliance between Gibeon and the Israelites, the neighboring Canaanite cities came together to attack Gibeon. The Gibeonites sent word to Joshua, and the Israelites marched through the night to successfully relieve the siege and inflict a significant defeat on the Canaanite coalition.

The biblical text makes no mention of Gibeon being destroyed as a result of this episode, and from an archaeological perspective, we only require that the city was occupied and presumably fortified at the time of the conquest. I say fortified, because the Gibeonites would have had to resist the assault of the Canaanite host for a minimum of two days to allow time for word to reach Joshua, the army of Israel to be mobilized, and the overnight march to Gibeon.

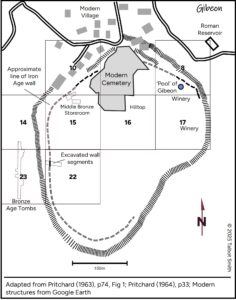

Figure 6: Wine jar handle stamped “GB’N” from Gibeon. Object 60-13-6 Courtesy of the Penn Museum

Ancient Gibeon is located on the south side of the modern Arab village of Al Jib, which preserves a portion of the ancient name. The site was excavated by James Pritchard of the University of Pennsylvania for five seasons between 1956 and 1962, and many artifacts from Gibeon can be found in the Penn Museum in Philadelphia. The association of Al Jib (or El-Jib) with Gibeon can be traced back to at least 1666 AD,[24] but this was questioned as Eusebius had placed it four miles west of Bethel, near Rama.[25] As it turns out, if we locate Bethel at Al-Bireh, the distance is approximately 4.25 English miles (4.5 Roman miles) as the crow flies, but more south than west. Al Jib is also about 2.7 miles due west of Rama (Al-Ram). Jerome’s translation of Eusebius might suggest that “west” meant west of the road between Jerusalem and Bethel as opposed to strictly west of Bethel itself.[26] Regardless, the identity of Al Jib as Gibeon was confirmed during the first four seasons of excavation by the discovery of thirty wine jar handles inscribed with “GB’N” in ancient Hebrew (See Figure 6).[27] Thus, unlike Ai, there is no question as to the identity of the site.

Figure 7: Archaeology of Gibeon

Gibeon turned out to be a challenging excavation, and contrary to established practice, Pritchard did not publish a stratification of the site. One of the specific challenges was that the summit of the mound had been badly disturbed by the digging of defensive trenches and by heavy shelling during the First World War. Also, a modern cemetery covers a large area near the top of the mound, preventing excavation of that area. In Pritchard’s words:

“In view of this somewhat erratic pattern of the stratigraphic evidence for the history of the mound, it has been deemed impracticable to assign letters or numbers to the general strata and to present the evidence in the final reports under a chronological arrangement.”[28]

He describes five levels of occupation, but only indicates four occupational periods: Early Bronze Age, Middle Bronze Age, Iron Age I and II, and Roman. It would seem that he distinguishes between the initial Iron I city and the later Iron II city. Based on the excavation reports and other publications, I will attempt what Pritchard would not, and provide a history of the site as shown in Figure 7. What is important with respect to our search is the absence of evidence of an occupation during the Late Bronze Age. Pritchard notes an almost complete absence of Late Bronze Age pottery sherds (fragments) on the tell.[29]

Figure 8: Excavations at Gibeon

In the course of the five seasons at Gibeon, a total of fifty-five Bronze Age tombs were discovered and excavated in areas 14 and 23 (See Figure 8). Of these, fifteen contained remains exclusively from the Middle Bronze I period. The remaining forty tombs contained remains from the Middle Bronze II (A, B, and/or C), either exclusively or in combination with remains from Middle Bronze I. Eight of these tombs also contained Late Bronze Age remains.[30] Similar t Jericho, the Late Bronze Age tombs contained Egyptian scarabs dating from the reigns of Thutmose III through Amenhotep III, confirming the dating of the associated pottery to the late LB I and LB IIA periods. On the basis of the finds in these tombs, and the tombs alone, Pritchard proposed that there must be some as yet undiscovered Late Bronze Age city on the tell.

“This seeming discrepancy between the biblical record and the actual remains at the site was suddenly resolved in 1960, when we opened two tombs to find in them a rich assortment of Late Bronze Age pottery. That they were no isolated burials of the nomads of the period seems certain from the fact that one of them, Tomb 10B, had the largest number of objects (147 catalogued objects and 73 beads) that we have yet found in a tomb at el-Jib. These richly furnished tombs of the Late Bronze period indicate that Gibeon was in existence in the period immediately before the time of Joshua, although we have thus far failed to find the particular area of the mound which the city of that period occupied.”[31]

Pritchard subscribed to our Theory Four, with an Exodus in the time of Ramesses II, and so was expecting to find Late Bronze IIB remains. He is suggesting that the tombs indicate an occupation in that time period, although there is no direct evidence of it. He does, however, refer to the fact that it was common in that period for nomadic peoples to use existing tombs, which resulted in burials in city cemeteries during periods when the associated city was abandoned. But in this case, he argues that the burials are too rich for mere nomads.

Normally, when a city is occupied, it generates a significant amount of pottery refuse, both in the area of the city and in dumps and fills around it. The almost total absence of Late Bronze pottery finds during the excavation (Pritchard found only two sherds in a dump) indicates that the tell was abandoned during that period or only very lightly occupied. Given this, we should consider an alternative explanation for the well-furnished Late Bronze tombs:

4 Now the king went to Gibeon to sacrifice there, for that was the great high place: Solomon offered a thousand burnt offerings on that altar. 5 At Gibeon the Lord appeared to Solomon in a dream by night; and God said, “Ask! What shall I give you?” (I Kings 3:4-5, NKJV)

And during the reign of David:

For the tabernacle of the Lord and the altar of the burnt offering, which Moses had made in the wilderness, were at that time at the high place in Gibeon. (I Chronicles 21:29, NKJV)

While David and Solomon are traditionally placed in the early Iron Age, the existence of a “high place” or cult center at Gibeon would have likely predated them. If Gibeon was an important cult center, then the Late Bronze Age burials can be assigned to either the priests of that place or cult followers who wished to be buried there. This explanation squares better with the evidence than what I believe was wishful thinking on the part of Pritchard in 1962. Indeed, Pritchard ultimately concluded three years later:

“There was no extensive city on the tell from the end of Middle Bronze until the beginning of the twelfth century. The Late Bronze tombs of the fourteenth century belonged either to a very small settlement, limited to some small section of the mound as yet untouched, or to the temporary camps in the vicinity. There can be no doubt, on the basis of the best evidence available, that there was no city of any importance at the time of Joshua.”[32]

Again, Pritchard assumes the “time of Joshua” to be the Late Bronze IIB, but his statement is applicable to the whole of the Late Bronze Age.

The Middle Bronze Age occupation is not entirely without problems either. Significant amounts of Middle Bronze II pottery were found on the tell, so there is no question that the city was occupied during that period. Pritchard also found the remains of a storeroom in Area 15 with Middle Bronze IIB pottery buried under a thick layer of ash and debris, indicating a fiery destruction. Pritchard consistently identifies this pottery as matching that which Kenyon found in the remains of Jericho City IV and its Middle Bronze tombs.[33] What Pritchard does not report is the discovery of Middle Bronze Age city walls. Recall that to align with the story in Joshua, we need the city to be both occupied and fortified. It would be quite unusual for a city of the Middle Bronze IIB/C period, the size of Gibeon, to be unfortified, given the fortifications found at every other city of this period. This leaves us with three possibilities. First, Pritchard’s excavations may not have located the Middle Bronze fortifications (unlikely). Second, the Iron Age fortifications were built along the same course as those from the Middle Bronze, leaving no remains, or perhaps causing Pritchard to mis-date the walls. A third option was suggested by John Bimson:

“If the MBA city was without defences, as appears to have been the case, this would explain why, even though it was large, it sought to make peace with the Israelites rather than oppose them, and also why it begged help from the Israelites when threatened by the Amorite alliance (Jos 10:6).”[34]

I will speculate that, if Gibeon’s identity as a cult center stretched back to the Middle Bronze period, then perhaps it was a “free city” as Olympia was to the Greeks a thousand years later, and this would explain the absence of walls. Clearly, Gibeon was occupied, but perhaps we should not require it to be fortified.

The findings of a destruction by fire in the Middle Bronze remains, and the evidence that the city was abandoned for centuries following that period, raise a question as to what happened following the events of Joshua 10. We might consider that the evidence of burning is the result of the assault by the Canaanite coalition that attacked Gibeon prior to Joshua’s arrival, particularly if the city was unwalled. But what about the abandonment of the city? Recall from Joshua 9:23 that the Gibeonites were destined to be slaves to the Israelites. It is likely that, following his southern campaign, Joshua removed the Gibeonites from their city to the Israelite camp at Gilgal, either to protect them from further attacks, to begin their service, or both. The city would then at least be abandoned, and he may have destroyed it to prevent it from being reoccupied by other Canaanite groups.[35]

When we consider our Theories in the context of Gibeon, only Theory One fits the evidence. An Exodus with the Hyksos expulsion could also fit, as long as there is no extended period of wilderness wanderings, allowing the conquest to still occur in the Middle Bronze Age. Both Theory Three and Four are ruled out, unless you subscribe to Pritchard’s wishful thinking.

Hazor

Our last stop is the great city of Hazor, in the north of Israel—the largest city by far in all of Canaan at the time of the conquest. Following a battle in which the Israelites defeated a coalition of cities led by the king of Hazor, the book of Joshua records:

10Joshua turned back at that time and took Hazor, and struck its king with the sword; for Hazor was formerly the head of all those kingdoms. 11And they struck all the people who were in it with the edge of the sword, utterly destroying them. There was none left breathing. Then they burned Hazor with fire.

12So all the cities of those kings, and all their kings, Joshua took and struck with the edge of the sword. He utterly destroyed them, as Moses the servant of the LORD had commanded. 13But as for the cities that stood on their mounds, Israel burned none of them, except Hazor only, which Joshua burned. (Joshua 11:10-13, NKJV)

Judges 1 further lists a number of northern cities that the Israelites were unable to conquer. Altogether, these statements leave Hazor as the only city in northern Canaan where a destruction is recorded, and thus Hazor is the only site where we might look for evidence of the conquest.

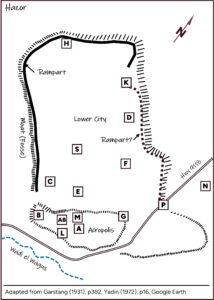

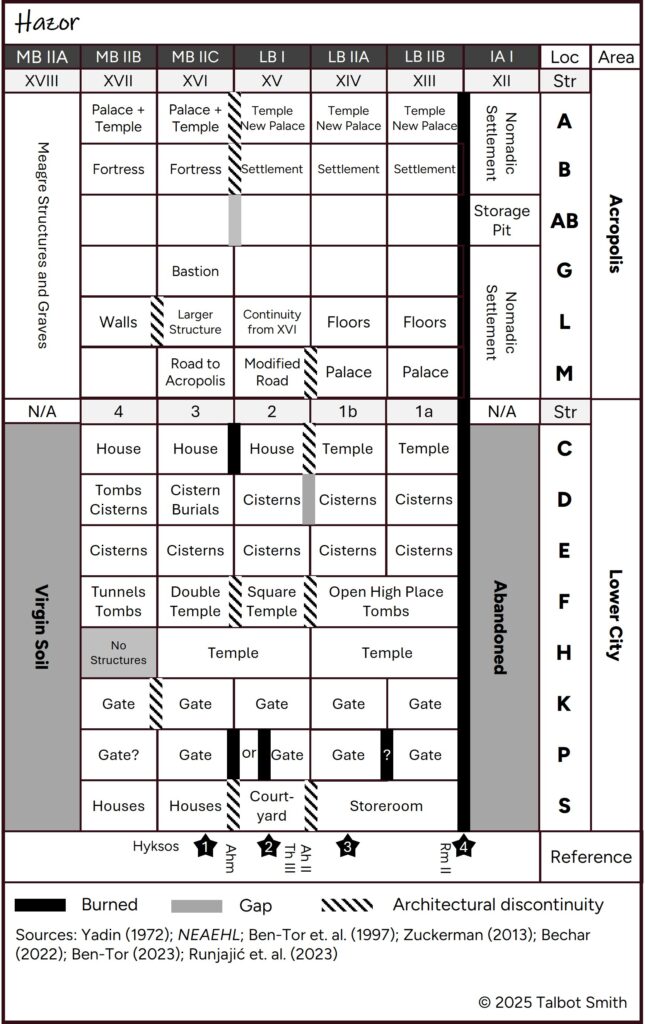

Figure 9: Excavations at Hazor

Bronze Age Hazor consisted of two parts: An acropolis, or hilltop, and a large lower city (See Figure 9). The site was first excavated by John Garstang in 1928, but Garstang never published any detailed findings. A much more extensive excavation was conducted by Yigel Yadin over four seasons between 1950-58 and a fifth season in 1968-69. Further excavations were conducted beginning in 1990 under the direction of Amnon Ben-Tor and continuing to the present, now directed by Shlomit Bechar. These excavations have focused on the acropolis, except for some additional excavations in Area S. However, even after all of this time, only approximately two and a half percent of the total area of the city has been excavated.[36]

For those of you who are fans of our Theory Four, the Exodus in the time of Ramesses II, this is your moment. As William Dever is fond of pointing out, Hazor is almost the only city that fits the Joshua narrative for a conquest in this time period.[37] There is no question that Hazor was destroyed at the end of the Late Bronze Age, and the manner of its destruction is what we would expect. Sharon Zuckerman, one of the recent excavators, describes the destruction:

“Remains of conflagration and violent destruction, including collapsed brick, heaps of charred beams, and ash piled up in many places to a height of 2 m or more, were identified in all of Hazor’s public buildings. This destruction is also accompanied by evidence of the burial and intentional mutilation of the statues of gods and kings, especially in the cult buildings.”[38]

The added detail of the mutilation of ‘carved images’ certainly fits a destruction by the Israelites, and most likely that was the case, just not in the time of Joshua. Back in Part II, we dismissed the possibility of an Exodus and conquest in this time period based on the evidence indicating that the Israelites were already established in Canaan sometime prior to the reign of Ramesses II, and likely much earlier. Add to that the evidence we have reviewed in this part at Jericho, Ai, and Gibeon, and a conquest at this late date is just not possible. We must look earlier.

Figure 10: Hazor Findings by Area

For many years, there was a consensus that Hazor was also destroyed at the end of the Middle Bronze Age. In his scholarly book on the Hazor excavations, Yadin wrote:

“The end of the MB II came as a result of a violent destruction. In the Lower City, as we have seen, the LB I City [Stratum 2] was separated from the previous stratum [the MB II Stratum 3] by a thick layer of ashes. In the Upper City there is an indication of a short interval between the MB II City’s (XVI) destruction and the rebuilding of the LB I City.”[39]

This finding of a destruction layer at the end of the Middle Bronze Age was taken for granted for decades.[40] Indeed, if I were writing this as little as ten or fifteen years ago, this might be the end of our discussion. However, beginning with the publication of the 1968-69 season in 1997, the perspective began to shift as new findings and new interpretations emerged from the next generation of archaeologists (many of whom held lesser roles in the earlier digs). Where Yadin had described a destruction of the entire city, Ben-Tor described the transition at the end of the Middle Bronze Age as “smooth and uninterrupted” in Area A of the acropolis.[41] At the same time, he noted evidence of destruction in Areas C, K, and P.[42] The scope of destruction would erode further with an analysis of the remains of the gate in Area K, which found no “evidence for destruction between the [Middle (3) and Late Bronze (2)] strata.”[43] This leaves just two areas where burning is evident, C and P. Of Area C, Shlomit Bechar, the current excavator, writes:

“At the end of Stratum 3, Building 6200 was covered by a layer of ashes (Yadin et al. 1960, 77), leading Yadin to suggest that this stratum came to an end in a violent conflagration (Yadin 1972, 31). However, since this is of limited extent in Area C in general, this might seem an exaggeration. It would be more cautious to say that Building 6200 came to an end in a fire, but not necessarily the entire Stratum 3 of Area C, and of course not the entire stratum of the lower city.”[44]

Furthermore, Bechar prefers to date the destruction of the gate in Area P to LB I as opposed to MB II, which leaves us basically nothing. Figure X summarizes the archaeological findings at Hazor, based on the latest information. In Area P, the stratification is unclear, and the original excavator, Amihai Mazar, presented two options for dating the destruction: the end of MB IIC or during LB I. Mazar preferred the first option of an MB IIC destruction. Having reviewed the relevant material, I observe the following:

-

- If the evidence of burning in Area C Stratum 3 (MB IIC) is related to a destruction, then we should align it with other evidence of disturbance in the Lower City. This would suggest the burning of the gate in Area P is from the same time period.

- Architectural discontinuities may be evidence of destruction. They could, of course, also reflect “urban renewal” projects. And the destruction need not be the result of a conquest. For example, an earthquake could have the same effect.

- Considering both points above, Hazor evidences some sort of crisis at the end of both Stratum 3 (MB IIB/C) and Stratum 2 (LB I) in addition to the final destruction at the end of the LB IIB (Stratum 1a).

In the lower city, the crisis at the end of MB IIB/C seems to have been confined to the southern portion (Areas C, F, P, and S) while the northern area (Areas H, K) was seemingly unaffected. Here I should note that due to the nature of Areas D and E, they may be unlikely to retain destruction debris and perhaps should be excluded from our consideration.[45] With respect to the upper city, Ben-Tor notes:

“Although the renewed excavations did not uncover evidence of destruction or of any settlement gap between the Middle and Late Bronze Ages, they clearly indicated that during this period, in the fifteenth century BCE, the entire area in the middle of the acropolis underwent a total reorganization.”[46]

What are we to make of all this? First, if the destruction of Hazor mentioned in Joshua was not at the end of the Late Bronze Age (Theory Four), the only other evidence of burning, and thus the only other option, is at the end of the Middle Bronze Age (Theory One or a modified Theory Two). While there is evidence that Hazor experienced some sort of crisis during or at the end of the Late Bronze I period (Theory Two or Three), no evidence of burning has yet been found associated with this period, other than the possible destruction of the gate in Area P. In the Middle Bronze IIB/C conquest scenario, this crisis could be the result of continued Israelite pressure (Judges 4:24), while the Late Bronze I crisis could be the result of Thutmose III’s conquests.

Second, if we wish to place the conquest in the Middle Bronze IIB/C period, the evidence currently available to us from excavations at Hazor creates some challenges in interpreting the relevant passage in Joshua. The statement, “they burned Hazor with fire” (Joshua 11:11), would have to signify an incomplete destruction as indicated in Areas C and the gate in Area P. Interestingly, there is a parallel for this elsewhere in the conquest account. In Judges Chapter 1, we find:

Now the children of Judah fought against Jerusalem and took it; they struck it with the edge of the sword and set the city on fire. (Judges 1:8, NKJV)

But in the same chapter, we also find:

But the children of Benjamin did not drive out the Jebusites who inhabited Jerusalem; so the Jebusites dwell with the children of Benjamin in Jerusalem to this day. (Judges 1:21, NKJV)

These two passages seem difficult to reconcile, but fortunately, Josephus gives us the details of what happened:

“…they besieged Jerusalem; and when they had taken the lower city, which was not long after, they killed all the inhabitants; but the upper city was not to be taken without great difficulty, through the strength of its walls, and the nature of the place.” Antiquities Book 5 2:2:124

The implication here is that the Israelites were unable to conquer Jerusalem completely and were forced to withdraw.[47] Given that Hazor had a similar configuration, with both an upper and lower city, it’s not hard to imagine a similar outcome, and that is what the archaeological evidence suggests. In this context, we should consider how to interpret:

But as for the cities that stood on their mounds, Israel burned none of them, except Hazor only, which Joshua burned. (Joshua 11:13, NKJV)

Based on the evidence, Joshua did not burn the acropolis of Hazor, which would be associated with the “mound” of that city. But he did burn Hazor, and specifically parts of the Lower City. Thus, an interpretive rendering could be:

But the other cities that stood on their mounds, Israel burned none of them. Hazor only [the Lower City], Joshua burned. (Joshua 11:13)

Overall, I find this situation at Hazor less than satisfactory. I am anxious to see additional excavations of Middle Bronze levels in the Lower City of Hazor, and particularly in the southern portion, to determine the scope of destruction. Until that happens, we should consider the archaeological evidence at that site to be a “definite maybe” in terms of supporting our Theory One, or any Exodus date during the Hyksos period that allows the Israelites to arrive in Canaan before the end of the Middle Bronze Age. The absence of evidence of burning in the Late Bronze I period (Stratum 2) is a problem for Theory Three.

All the Rest

Of the thirty-one cities listed in Joshua 12, twenty-one have been identified and reasonably excavated. This includes several whose identity is in dispute, such as that of Bethel. In addition to Gibeon, the cities of Hormah and Arad (Joshua 12:14, Numbers 21:1-3) also have a total absence of Late Bronze Age architectural remains. These sites were excavated by Yohan Aharoni between 1967 and 1975. Aharoni subscribed to the Late Bronze IIB conquest model (Theory Four), and in that context, he wrote:

“We therefore arrive at a most startling conclusion: the biblical traditions associated with the Negeb battles cannot represent historical sources from the days of Moses and Joshua, since nowhere in the Negeb are there any remains of the Late Bronze Age. However, the reality described in the Bible corresponds exactly to the situation during the Middle Bronze Age, when two tels, and two tels only, defended the eastern Negeb against the desert marauders, and the evidence points towards the identification of these tels with the ancient cities of Arad and Hormah. Thus the biblical tradition preserves a faithful description of the geographical-historical situation as it was some three hundred years or more prior to the Israelite conquest.”[48]

Of course, if we place the conquest in the Middle Bronze Age, the existence (and destruction) of these cities would line up precisely with the Israelite conquest. As discussed above, we might also place Ai and Jericho in the category of not existing in the Late Bronze Age, or at least, in the case of Jericho, not having the requisite characteristics during that period. Of the thirty cities that have been excavated, there is only one period where all of them were occupied, and that is the Middle Bronze IIB/C. Beyond Jericho and Ai, there is a wide pattern of destruction layers in that period, including many of those listed as defeated or “put to the sword” by Joshua. Some, such as Gibeon, Hormah, and Arad, are vacant for all of the Late Bronze Age. Others have occupational gaps only for part of this period. Thus, only a conquest in the Middle Bronze IIB/C would fully align the archaeological evidence with the biblical text.

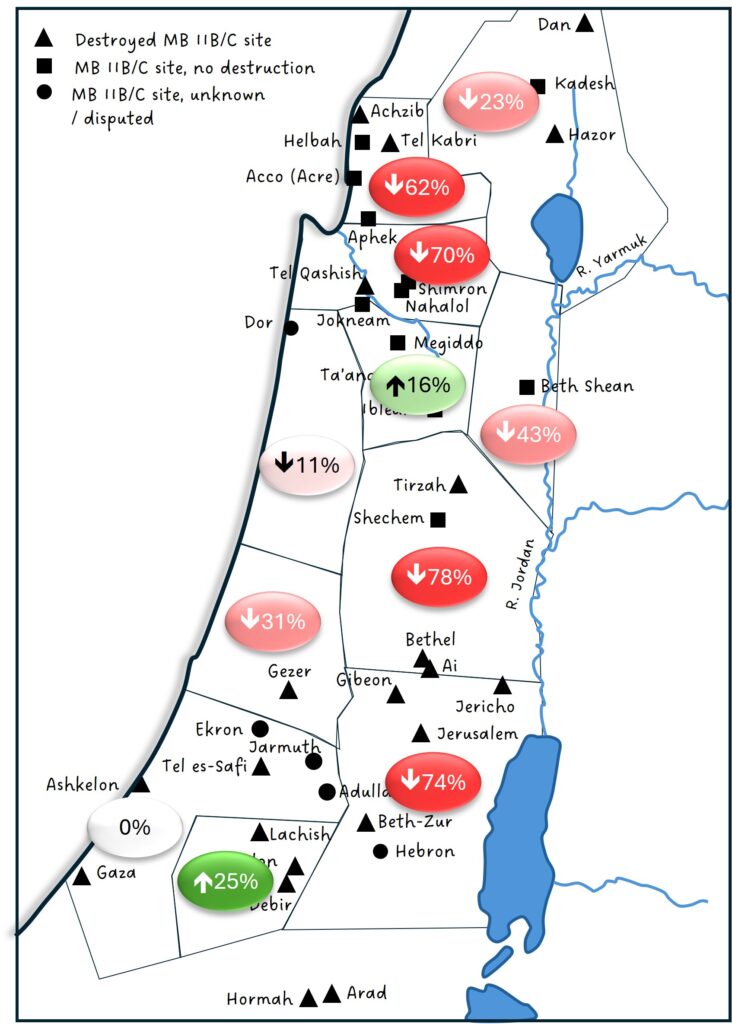

Changes In Population

At the beginning of this Part III, I made the case that we should not expect a change in the material culture in Canaan with the arrival of the Israelites. They had come from Canaan to Egypt, where their material culture, and particularly their pottery, retained a strong Canaanite influence. After forty years as nomads in the desert, they would have likely lost the ability to produce their own pottery, instead purchasing it from Canaanite sources. There is, however, one aspect of Israelite culture that clearly sets them apart from the Canaanites that they replaced: While the Canaanites were city dwellers, the Israelites were nomads, dwelling in tents. This is not to say that the Israelites did not occupy some of the cities they conquered. Clearly, they did. However, Joshua describes many cities in the hill country and south as “destroyed”, even if they were not explicitly burned, and all indications are that the Israelites continued to be “nomadic pastoralists” well into the Iron Age. As it turns out, there is evidence for just such a transition between the Middle Bronze Age and the Late Bronze Age.

In the 1980s, Israel Finkelstein and his colleagues conducted extensive surveys of archaeological sites across modern Israel, culminating in several publications in the early to mid-1990s. In a 1992 article, Finkelstein examined the distribution of sites and estimated population during the Middle Bronze Age, and in 1996, he did the same for the Late Bronze Age.[49] Both studies specifically measured the settled population, i.e., those living in permanent settlements such as cities, towns, and villages. Nomadic populations are very difficult to measure because they leave little to no trace in the archaeological record, and so they are not reflected in Finkelstein’s population estimates. The information from the two papers is compared in Figure 11, which shows the net percentage change in population from the Middle Bronze Age to the Late Bronze Age in specific regions of Canaan.

Figure 11: Population Changes in Canaan from the Middle Bronze Age to the Late Bronze Age

What is notable is that the most significant population declines were in exactly the areas successfully conquered by the Israelites. In contrast, the southwest coast, which remained unconquered, maintained a steady population. Population increases are noted in the area of Megiddo, which would remain a Canaanite stronghold (Judges 1:27), and Lachish, which Joshua had conquered. In both cases, I would suggest that the population swelled with refugees from other areas of Canaan. Lachish, being adjacent to the unconquered coastal area and on the periphery of Judah, was likely rebuilt by the coastal Canaanites. Alternatively, Lachish may have been one area where the Israelites chose a more settled lifestyle, boosting the population.

Conclusions

At last, we come to the conclusion of our search for the Exodus Pharaoh. Having considered all of the evidence, it is time to review our theories and decide which one has the greatest merits.

Theory Four: Theory Four, otherwise known as the Late Exodus Theory or the Ramesside Exodus Theory, completely fails when it comes to the archaeological evidence. In this time period, there is, with the exception of Hazor, no evidence of the conquest. This has led many of those who espouse this theory to conclude that the conquest is a mere myth and to search for other explanations of the origin of a people called Israel. However, as we saw in Part II, there is plenty of evidence that Israel was already in Canaan long before Ramesses II was even born.

We can safely dismiss Theory Four, but rather than dismiss the Exodus and conquest as historical events, we should look for them in a different time period.

Theory Three: Moving backward in time, we have the “Early” Exodus Theory, with Amenhotep II in the role of Exodus Pharaoh. This predates the evidence for Israel’s presence in Canaan (unless the Berlin Pedestal comes from this Pharaoh or earlier), so no problem there. However, Theory Three struggles with the archaeological evidence in both Egypt and Canaan. The evidence at Jericho is hotly debated, as is the assertion that Ai was destroyed in this period. Most importantly, though, is the absence of occupation at several key sites during the Late Bronze I, notably Gibeon, Hormah, and Arad, but also Debir if we associate it with Tel Beit Mirsim (which has been disputed). There is also the lack of any evidence of destruction at Hazor in this period, with the possible exception of the gate in Area P. In Egypt, there is no significant Semitic population in Avaris at this time to participate in the Exodus. Also, the military strength of both Amenhotep II and his father, Thutmose III, makes an Exodus in this time period unlikely.

Theory One and Theory Two: This then brings us back to where we started, and the two oldest of our four theories, which happen to correspond to the earliest potential dates and Pharaohs. A conquest in the Middle Bronze IIB/C period, and not necessarily at the very end, would fit all of the archaeological evidence in Canaan, save for the lack of a broad destruction at Hazor. Most importantly, all of the sites in Joshua 12 are occupied in this period. If we consider the known additional sites listed in Judges 1, we also find them occupied in this period. Thus, the archaeological fit is very good. In Egypt, we have a large Semitic population at Avaris to support either theory. However, if we take Theory Two literally, an Exodus at the time of Ahmose, coupled with forty years of wilderness wanderings, would bring Israel into Canaan early in Late Bronze I, a bit too late for the archaeology. This leaves us with Theory One or a modified version of Theory Two, where the Exodus occurs earlier in the Hyksos period, with time for the conquest to occur before the end of the Middle Bronze IIB/C.

Who then is the Pharaoh of the Exodus? Based on Josephus, it would seem that Dudimose is the correct choice. While a Hyksos Pharaoh could fit the bill, none have been suggested by any of the ancient sources.

The Chronology Problem

But what about I Kings 6:1? If we choose Dudimose as our Exodus Pharaoh, he is way too early based on the conventional understanding of Egyptian history and chronology. I Kings 6:1 places the Exodus four hundred eighty years before the fourth year of Solomon, or in 1446 BC by the generally accepted dating of the Israelite kings, with the conquest beginning forty years later in 1406 BC. The end of the Middle Bronze Age is generally dated to 1550 BC, leaving a gap of at least one hundred fifty years. To this, I will offer four potential solutions:

Option 1: The absence of evidence for an Exodus and conquest in the Late Bronze Age (Theory Three or Four) indicates that these events never happened. This is very much the secular view.

Option 1a: Secular archaeologists have long assigned the destructions at the end of the Middle Bronze Age to a sort of revenge tour on the part of Pharaoh Ahmose after he expelled the Hyksos. Because we know that Ahmose destroyed Sharuhen, the last Hyksos stronghold located in southwest Canaan (though where exactly is disputed), it is assumed that he is also responsible for all of the other destructions of this period, simply because there are no other candidates in their minds.[50] An invasion from the north has also been proposed, and of course, some of the city destructions could be due to local infighting or the invasions of Bedouin from the east, but the Israelites don’t enter into the conversation.[51]

Option 1b: Another approach we might expect from the secular archaeology community would be to acknowledge that the Joshua account contains elements passed down in oral histories from groups that later became part of the nation of Israel. This would be the perspective of the quote above from Yohan Aharoni. Thus, perhaps some Bedouin group (but not the entire Israelite nation) from east of the Jordan was responsible for the destruction of Jericho, and this memory was retained and became part of Israel’s national identity when that group merged into the large community of Israel. This is sort of a middle ground that recognizes that something happened but stops short of recognizing the biblical text as correctly recording those events.

In both Options 1a and 1b, the early dating of the evidence for a conquest is a reason for denying that the conquest occurred as described in Joshua. However, there are other options for those of us who believe the biblical account of the conquest is historical.

Option 2: In my article on Judges, I have provided a table which shows that the total years from the Exodus to Solomon, based on the Judges text and using Josephus to fill in the gaps, is just over six hundred years. Six hundred years before Solomon would be 1566 BC for the Exodus and 1526 BC for the conquest, which happens to correspond to the radiocarbon dating of burned seeds from Jericho City IVc.[52] This would, of course, require a non-literal interpretation of I Kings 6:1. Here, I would suggest that rather than referring to twelve idealized generations of forty years, we might interpret it as referring to twelve epochs, or periods of unknown length, that are idealized to forty years. This would allow us to accept the evidence within the orthodox chronology for Egypt.

Option 3: The final alternative is to consider an alternative chronology for Egypt, one that moves the Pharaohs and their archaeological periods to the right on the timeline and allows a 1446 BC Exodus and 1406 BC conquest to fall in the Middle Bronze Age, aligning with the archaeological evidence. Exactly this solution has been proposed by David Rohl in his New Chronology, and by other scholars who support the Centuries of Darkness chronology, first proposed by Peter James. Rohl’s chronology is perhaps best known from the Patterns of Evidence films and earlier BBC documentaries. These chronologies identify a different Pharaoh as the biblical Shishak, allowing the Third Intermediate Period of Egyptian history to be compressed to better reflect the archaeology. The result is to shift the dates for earlier Egyptian history later. The archaeological periods are very much tied to the Pharaohs by the pottery and other evidence, particularly scarabs, and so these periods move as well. The result of these changes is that the end of Middle Bronze IIB/C moves to somewhere after 1400 BC and Dudimose can be the Exodus Pharaoh while retaining a literal interpretation of I Kings 6:1

It’s important to understand that the archaeological community will mostly land on a variant of Option 1. For those who believe that the Bible recorded the events of Joshua correctly, the evidence suggests some variant or combination of Option 2 or Option 3.

Footnotes

[1] The Dead Sea Scrolls are over 1,500 years younger than what we would be looking for, and only survived because of the incredibly dry climate on the margins of the Dead Sea.

[2] This is the term preferred by William Dever in his writings. It describes a people whose living is made in animal husbandry and who shift their location with the seasons to find pasture for their animals.

[3] Bietak (1991), p. 29

[4] Dever (1990), p. 47

[5] Since the time of Albright, the prevailing opinion among archaeologists has been that the conquest must have happened shortly before the first mention of Israel on the Merneptah stele, i.e. at the time of Ramesses II and our Theory Four. The material culture changes that accompanied the Late Bronze Age Collapse are generally cited as evidence for the emergence of a new people group, and this seems to have prevented the consideration of any other options.

[6] Kenyon (1957), pp. 262-63

[7] See Wood (1990).

[8] See Bimson (1981).

[9] See in particular James (1993), Centuries of Darkness, and Rohl (1995), A Test of Time, for a detailed explanation of why this revision is not only possible but desirable. Rohl’s chronology was also featured in the Patterns of Evidence films.

[10] See Albright (1924), pp. 141-49

[11] See Kelso (1968)

[12] Callaway (1976)

[13] Albright (1924), p. 146

[14] Callaway (1968), p. 312

[15] See Livingston (1970), which can be found on the Associates for Biblical Research website. See the link in the References section.

[16] A Roman mile is 5,000 feet or 0.95 English miles. See Livingston (1970), Figure 1, which is not found in the original article, but in the ABR reissue. The milestone that Livingston claims to be the eleventh was originally identified as milestone “X”, the Roman numeral for ten.

[17] Livingston (1994). See Finkelstein, Lederman, & Bunimovitz (1997), pp. 512-13 for the site survey.

[18] Wood (2008), p. 213

[19] See Wood (2008) and Wood (2016). The earlier article can be found on the ABR website, and the latter on Academia. See References

[20] See Finkelstein, Lederman, & Bunimovitz (1997). The site identified as Khirbet el-Maqatir (17-14/36-01, pp. 519-20) is the later Byzantine monastery. The site excavated by Wood is 17-14/36-02 on pp. 521-22.

[21] Rohl (2014), pp. 285-6. The scarab was published in 2016 and is addressed in Rohl (2021), Part Two, p. 42-4

[22] David Rohl, personal correspondence.

[23] See Wood (1990).

[24] Pritchard (1962b), p. 29

[25] Eusebius, Onomasticon, entry for “Gabaon”. Eusebius, from the Greek: “Now there is a village called by this name near Bethel, about four milestones west. It lies near Rama.” (Eusebius (2003), pp. 41-2)

[26] Jerome, from the Latin: “Now a village of the same name is shown four milestones from Bethel on the western side near Rama” (Eusebius (2003), pp. 41-2)

[27] Pritchard (1961a), p. 2 The excavations would ultimately find over 60 of these handles

[28] Pritchard (1964), p. v

[29] Pritchard (1962b), pp. 135-6

[30] Pritchard (1963), tables p. 2-3

[31] Pritchard (1962b), p. 136

[32] Quoted from Pritchard (1965), “Culture and History”, in Hyatt (ed ), The Bible in

Modern Scholarship, Nashville, pp. 313-24, by Bimson (1981), p. 192

[33] See Pritchard (1963) for the details of the tombs and Pritchard, et al (1964), p. 42-46 for the Middle Bronze storeroom. The latest Middle Bronze pottery found in the tombs matches Kenyon’s Group V, representing the terminal phase of occupation at Jericho. The pottery in the destroyed storeroom is slightly earlier, matching Kenyon’s Group III.

[34] Bimson (1981), p193

[35] Ibid

[36] Ben-Tor (2023). This includes roughly 18% (3 acres) of the upper city and 1% (2 acres) of the lower city

[37] See in particular Dever (1990), p. 61 and tables pp. 57-60

[38] Zuckerman (2013), p. 97

[39] Yadin (1972), pp. 124-25

[40] See for example, Weinstein (1981), Bimson (1981)

[41] Ben-Tor et. al. (1997), p. 4

[42] Ibid

[43] Runjajić et. al (2023), p. 13. More specifically, this work found no evidence of the Middle Bronze Age gate being burned.

[44] Bechar (2022), p. 45

[45] See Bechar (2022), p. 66. Bechar excludes these areas from her analysis for similar reasons.

[46] Ben-Tor (2023), p. 79

[47] See Regev et al (2021) for evidence of burning in Middle Bronze Age Jerusalem

[48] Aharoni (1976), p. 73

[49] Finkelstein (1992), Finkelstein (1996)

[50] See, for example, Weinstein (1981)

[51] See Naaman (1994) for a proposal that the Hurrians were responsible at least for the northern destructions (largely those that Joshua 11:13 and Judges 1 identify as not destroyed by the Israelites).

[52] Nigro & Yasine (2024), p. 53. Based on radiocarbon dating, they place the destruction of City IVc between 1550 and 1525 BC.

References

The following is a list of the works referenced above. Where available, I have provided links to the material. However, note that many of these require a subscription. Major university libraries typically have such subscriptions, and if you have access to one, you may be able to access the articles that way.

Aharoni, Y. (1976). Nothing Early and Nothing Late: Re-Writing Israel’s Conquest. The Biblical Archaeologist, 55-76. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3209354

Amiran, R. (1970). Ancient Pottery of the Holy Land: From its Beginnings in the Neolithic Period to the End of the Iron Age. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Bechar, S. (2022). Political Change and Material Culture in Middle to Late Bronze Age Canaan. University Park, Pennsylvania: Eisenbrauns.

Ben-Tor, A. (2023). Hazor: Canaanite Metropolis, Israelite City (Expanded 2023 ed.). Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

Ben-Tor, A., Bonfil, R., Garfinkel, J., Greenberg, R., Maeir, A., & Mazar, A. (1997). Hazor V. Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society; The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Bietak, M. (1991). Egypt and Canaan During the Middle Bronze Age. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 27-72. doi:10.2307/1357163

Bimson, J. J. (1981). Redating the Exodus and Conquest. Sheffield: The Almond Press. https://biblicalarchaeology.org.uk/pdf/bimson/redating-the-exodus-and-conquest_bimson.pdf

Callaway, J. A. (1968). New Evidence on the Conquest of Ai. Journal of Biblical Literature, 87(3), 312-320. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3263542

Callaway, J. A. (1976). Excavating Ai (Et-Tell): 1964-1972. The Biblical Archaeologist, 39(1), 18-30. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3209413

Dever, W. G. (1990). Recent Archaeological Discoveries and Biblical Research. Seattle: University of Washington Press

Eusebius. (2003). The Onomasticon. (J. E. Taylor, Ed., & G. S. Freeman-Grenville, Trans.) Jerusalem: Carta.

Finkelstein, I. (1992). Middle Bronze Age ‘Fortifications’: A Reflection of Social Organization and Political Formations. Tel Aviv, 19, 201-220.

Finkelstein, I. (1996). The Territorial-Political System of Canaan in the Late Bronze Age. Ugarit-Forschungen, 28, 221-255.

Finkelstein, I., Lederman, Z., & Bunimovitz, S. (1997). Highlands of Many Cultures: The Southern Samaria Survey, The Sites. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University. Retrieved from https://tau.alma.exlibrisgroup.com/view/UniversalViewer/972TAU_INST/12437174030004146?c=&m=&s=&cv=

Garstang, J. (1931). Joshua Judges. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Kregel Publications.

Garstang, J. and Garstang J. B. (1948). The Story of Jericho (2nd ed.). London: Marshall, Morgan, & Scott, Ltd.

James, P. (1993). Centuries of Darkness (US ed.). London: J. Cape.

Josephus, F. (1999). The Complete Works of Josephus. (P. L. Maier, Ed., & W. Whiston, Trans.) Grand Rapids, Michigan: Kregel Publications.

Kelso, J. L. (1968). The Excavation of Bethel (1934-1960). Cambridge, Mass: The American Schools of Oriental Research. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3768539

Kenyon, K. (1957). Digging Up Jericho. New York: Frederick A. Praeger.

Kenyon, K. (1981). Jericho III. Oxford: University Press

Livingston, D. (1970). The Location of Biblical Bethel and Ai Reconsidered. Westminster Theological Journal, 33(1), 20-44.

Livingston, D. (1994). Further Considerations on the Location of Bethel at El-Bireh. Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 126(2), 154-59. Retrieved from https://biblearchaeology.org/about/founders-corner/3572-further-considerations-on-the-location-of-bethel-at-elbireh

Na’aman, N. (1994). The Hurrians and the End of the Middle Bronze Age in Palestine. Levant, XXVI, 175-187.

Nigro, L. (2020). The Italian-Palestinian Expedition to Tell es-Sultan, Ancient Jericho (1997–2015): Archaeology and Valorisation of Material and Immaterial Heritage. In R. T. Sparks, B. Finlayson, B. Wagemakers, & J. M. Briffa (Eds.), Digging Up Jericho: Past Present and Future (pp. 175-214). Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology.

Nigro, L., & Yasine, J. (2024). Interim Report on the Excavations at Tell es-Sultan, Ancient Jericho (2019-2023): The Bronze and Iron Age Cities. Vicino Oriente XXIX, 47-96.

Pritchard, J. B. (1959). The Wine Industry at Gibeon. Expedition, 2(1), 17-25. Retrieved from https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/the-wine-industry-at-gibeon-1959-discoveries/

Pritchard, J. B. (1961a). The Bible Reports on Gibeon. Expedition, 3(4), 2-7. Retrieved from https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/the-bible-reports-on-gibeon/

Pritchard, J. B. (1961b). The Water System of Gibeon. Philadelphia: The University Museum, University of Pennsylvania.

Pritchard, J. B. (1962a). Civil Defense at Gibeon. Expedition, 5(1), 10-17. Retrieved from https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/civil-defense-at-gibeon/

Pritchard, J. B. (1962b). Gibeon, Where the Sun Stood Still. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Pritchard, J. B. (1963). The Bronze Age Cemetery at Gibeon. Philadelphia: The University Museum, University of Pennsylvania.

Pritchard, J. B., Reed, W. L., Spence, D. M., & Sammis, J. (1964). Winery, Defenses, and Soundings at Gibeon. University Park: University Museum, University of Pennsylvania.

Regev, J., Gadot, Y., Roth, H., Uziel, J., Chalaf, O., Ben-Ami, D., . . . Boaretto, E. (2021). Middle Bronze Age Jerusalem: Recalculating its Character and Chronology. Radiocarbon, 1-31. doi:10.1017/RDC.2021.21

Rohl, D. M. (1995). A Test of Time: The Bible – From Myth to History. London: Century.

Rohl, D. M. (2015). Exodus: Myth or History? St. Louis Park, Minnesota: Thinking Man Media.

Runjajić, M., Garfinkel, Y., Hasel, M. G., Yasur-Landau, A., & Friesem, D. E. (2023). Fire at the gate of Hazor: A micro-geoarchaeological study of the depositional history of a Bronze Age City gate. Journal of Archaeological Science, Reports, 49, 1-18. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2023.103914

Stern, E. (Ed.). (1993). The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land (Vols. 1-4). New York: Simon & Schuster.

Weinstein, J. M. (1981). The Egyptian Empire in Palestine: A Reassessment. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 1-28. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1356708

Wood, B. G. (1990). Did the Israelites Conquer Jericho? A New Look at the Archaeological Evidence. Biblical Archaeology Review, 16(2), 44-59. Retrieved from https://library.biblicalarchaeology.org/article/did-the-israelites-conquer-jericho-a-new-look-at-the-archaeological-evidence/

Wood, B. G. (2008). The Search for Joshua’s Ai. In G. A. Richard S. Hess (Ed.), Critical Issues in Early Israelite History (pp. 205-240). Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. Retrieved from https://biblearchaeology.org/images/archaeology/The-Search-for-Joshuas-Ai.pdf

Wood, B. G. (2016). Locating ‘Ai: Excavations at Kh. el-Maqatir 1995–2000 and 2009–2014. In T. Aharon, & Z. Amar (Eds.), In the Highland’s Depth (pp. 17-49). Ariel: Ariel University. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/28750045/Locating_Ai_Excavations_at_Kh_el_Maqatir_1995_2000_and_2009_2014_pdf

Yadin, Y. (1972). Hazor: The Schweich Lectures. London: Oxford University Press.